Like France, but unlike the Ireland or the United Kingdom, the United States combines the job of Head of State and Head of Government into a single person. A citizen can disagree with governmental policy proposals of Barack Obama, just as a citizen could disagree with the the policies of Ronald Reagan. But there is no reasonable doubt that Reagan did an excellent job in his role as Head of State. A patriotic American can appreciate the good work of a President as Head of State, even while disliking much of the President's work as Head of Government. Senator Obama's victory speech in South Carolina suggests that he too might be an outstanding Head of State.

Saturday, January 26, 2008

The Federal Communications Commission is proposing to fine 52 ABC stations $1.4 million for airing an episode of "NYPD Blue" in 2003 in which one scene contains "multiple, close-up views" of a woman's "nude buttocks." From the AP report:

FCC's definition of indecent content requires that the broadcast "depicts or describes sexual or excretory activities" in a "patently offensive way" and is aired between the hours of 6 a.m. and 10 p.m.

The agency said the show was indecent because "it depicts sexual organs and excretory organs , specifically an adult woman's buttocks."

The agency rejected the network's argument that "the buttocks are not a sexual organ."

Related Posts (on one page):

- The FCC's Linguistic Incompetence:

- NYPD Blue's Expensive Rear View:

If you've ever had even a passing interest in the Jewish community of Kaifeng, China, you will find this article, describing the wedding in Israel of a descendant of that community to an American immigrant, of interest.

Sixty years ago, when Egypt occupied Gaza, it refused to grant the local Arab residents, native Gazans and refugees from the Arab-Israeli war of 1947-48, citizenship. Instead, the Egyptian government intentionally cut them off from Egypt and kept them impoverished, so they could be used as a propaganda and military weapon against Israel. When Israel took over Gaza in 1967, it opened the border with Israel, providing tens of thousands of jobs for Gazans, and increasing the standard of living there dramatically, albeit from very low levels. After a wave of suicide attacks from Gaza, Israel gradually closed off the border with Israel, and finally closed it off entirely when Hamas took over last year. Meanwhile, Israel no longer occupies Gaza, and the population has sunken back into abject poverty.

With the Gazan's breach of the border with Egypt, and Egypt's refusal to use force to seal the border, things have come full circle. It's time to ask why Egypt, with 80 million people, can't grant Gaza's one million full Egyptian citizenship, and allow them to live in Sinai or even Cairo instead of being stuck in Gaza.

No matter what happens in the near future between the Palestinians and Israel, I doubt Israel will ever allow the reasonably free movement between Gaza and Israel that existed through the early 1990s. Giving the Gazans Egyptian citizenship, and making Egypt responsible for security in the area, would benefit Israel, the Gazans, and even Egypt itself, by destroying Hamas's base (Hamas being affiliated with Egypt's anti-government Muslim Brotherhood). It would also benefit the Palestinians in the West Bank, by allowing the more moderate residents there to reach an accommodation with Israel, perhaps in concert with Jordan.

If Israeli leaders had any p.r. sense and/or vision, they would use this opportunity to loudly ask why Egypt, which refused custody of Gaza when Israel returned the Sinai, is so adamant about refusing to do its part to relieve Palestinian suffering.

Friday, January 25, 2008

From the New York Times:

Mr. Obama’s campaign itinerary on Friday underscored his strategy in South Carolina: trying to elevate his appeal to white voters — women, in particular — even as he seeks to increase his support to black voters who state Democratic officials believe will comprise up to 60 percent of the primary electorate on Saturday.Except the original, still revealed via a google search, was:

Democrats Make Targeted Appeals to S.C. Voters - New York TimesUh-oh. (And yes, I'm sure I've done plenty of that myself, too; and people probably found it funny at the time.) Thanks to reader Paul Daly for the pointer.

... to increase his support to black voters who state Democratic officials believe will compromise up to 60 percent of the primary electorate on Saturday. ...

www.nytimes.com/2008/01/25/us/politics/25cnd-campaign.html?ref=politics - 1 hour ago - Similar pages

A student of mine is writing a very interesting article about restrictions on sex between medical and quasi-medical professionals (from psychotherapists and doctors to massage therapists and opticians) and patients. But he's looking for a good term to fill in the blank:

"One common argument for restricting sex between psychotherapists and their clients is that the clients often have a diminished ability to ___."

The term would mean something like "make wise decisions," but he'd like something shorter, preferably a single word (even if hyphenated). Of course, the claim isn't that all the rest of us are so good at making wise decisions about sex -- only that psychotherapists' clients tend to be even less able to make such decisions than the rest of us. Nor is the claim that the clients have a diminished ability to make wise decisions about sex with their psychotherapists; rather, it's that the emotional or mental problems that send them to the psychotherapist tend to cause a diminished ability to make wise decisions about sex more generally.

Note also that the question at this point isn't whether the argument is accurate, or whether, even if it's accurate, it justifies the regulations. My student is just looking for a clear yet concise term that can be used to fill in that blank (and can be reused many times later in the article, which is why my student is looking for something concise). If you have some tips for this, please post them in the comments. Thanks!

Like Orin, I'm supporting McCain for the Republican nomination. I disagree with him strongly about campaign finance reform and a few other issues. But he's taken the right stands, roughly speaking, on many other important matters, like national security, Iraq, torture, immigration, and fiscal responsibility. On federalism grounds, he's also opposed (and twice voted against) the Federal Marriage Amendment, a costly stand for a Republican presidential contender. I also think he's the one candidate in both parties who has sufficient credibility on security and military issues to end or modify Don't Ask, Don't Tell, and I detected somewhat lukewarm and perfunctory support for it in his answers on the question during the debates. Nobody's perfect, but his heart and mind seem closest to my own on most of the issues that matter most to me in this election.

Related Posts (on one page):

- Voting for McCain Tomorrow:

- I'll second that motion:

- Going With McCain:

I haven't had the pleasure of working with Zarov, but I have worked with Andy Frey ("Formerly a Deputy Solicitor General, Frey has argued more than 60 cases before the U.S. Supreme Court"), and have very much enjoyed it.

The list is here; Lawdragon reports that "The master of disaster [Klee] has kept a low profile the last few years preparing the definitive look at Supreme Court bankruptcy jurisprudence, building on his work for Boston Chicken, First Trust and Bank of New York." Ken is one of only a few professors who made the list; the others are Lucian Bebchuk, Jack Goldsmith, Elizabeth Warren (Harvard), Neal Katyal (Georgetown), Harold Koh (Yale), Mark Lemley (Stanford), Geof Stone (Chicago), and Jonathan Turley (George Washington).

Thanks to my colleague Steve Bainbridge for the pointer.

That's the question being addressed by speakers at a symposium I'm organizing. It's a first-of-its-kind event, devoted entirely to what has become an intramural debate among conservatives about the issue. The symposium will be held at the South Texas College of Law in Houston on February 15. Besides me, the speakers include:

Professor Gerard Bradley (Notre Dame)

Professor Jesse Choper (Berkeley)

Professor Teresa Collett (St. Thomas)

David Frum (AEI)

Charles Murray (AEI)

Professor Robert Nagel (Colorado)

Jonathan Rauch (Brookings)

Professor John Yoo (Berkeley)

Needless to say, it's an impressive group of academics and non-academics, many with strong ties to the conservative intellectual movement and/or expertise on the issue of gay marriage. Abstracts of the presentations can be found here.

If you'd like to attend, you can register for the symposium here. Registration is free and lunch is included.

Related Posts (on one page):

- Voting for McCain Tomorrow:

- I'll second that motion:

- Going With McCain:

The Honorable Douglas H. Ginsburg has announced that he will step down as Chief Judge of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit next month. Succeeding him will be the Honorable David B. Sentelle (for whom I clerked). As Howard Bashman notes, Judge Ginsburg's term as chief was not due to expire until July. Yet were he to wait until then, Judge Sentelle would be ineligible to become chief because he will be 65. By stepping down slightly early, Ginsburg enables Sentelle to become Chief shortly before his 65th birthday. Judge Sentelle is not eligible for a full seven-year term, however, as he will have to step down by the time he turns 70.

Here's how to deal with a recession: A federal government which is already spending more than its income should borrow even more money, so as to give lots of people a tax rebate. This is the bipartisan plan of President Bush and Congress. They are taking a leaf from the presidency of Jimmy Carter.

Even accounting for inflation, the Bush-Reid-Pelosi rebate is far more profligate than the proposed Carter rebate of 1977. But the two rebates appear to be based on the same demand-side principles.

President Carter also proposed tax rebates during the 1980 election campaign, as an alternative to Ronald Reagan's calls for tax cuts.

Some of the critics of Carternomics were known as "supply-siders." Ronald Reagan and his supporters argued that the best way to promote economic growth was not for the federal government to give people money, but for the government to cut marginal tax rates for the future, thereby spurring "supply-side" production and investment. The Bush tax cuts of 2001, and much of the tax policy of the rest of the Bush administration, were implementations of supply-side policy.

But the 2008 tax rebate brings us full circle back to 1980, as the final year of the Bush administration increasingly resembles the final year of the Carter administration-- including national malaise, getting tough on Israel but not on Palestinian terrorists, support for the DC handgun ban, the Olympics hosted by a communist regime with contempt for human rights, and a consensus that the current adminstration is lacking in competence.

There are important differences, of course. Including the probability that if the next President is a transformational one, that President will not an ideological successor of the genial, far-right Ronald Reagan, but instead will be the genial, far-left Barack Obama.

Thursday, January 24, 2008

Researchers at Yale and Columbia released the 2008 Environmental Performance Index this week. Switzerland and three Scandinavian nations topped the list. The United States did not do so well, however, ranking 39th of the 149 nations rated, largely because of the emphasis placed upon global climate change in the Index. As the New York Times reported:

“We are putting more weight on climate change,” said Daniel Esty, the report’s lead author, who is the director of the Yale Center for Environmental Law and Policy. “Switzerland is the most greenhouse gas efficient economy in the developed world,” he said, in part because of its use of hydroelectric power and its transportation system, which relies more on trains than individual cars or trucks.

The United States, with a score of 81.0, he noted, “is slipping down,” both because of low scores on three different analyses of greenhouse gas emissions and a pervasive problem with smog. The country’s performance on a new indicator that measures regional smog, he said, “is at the bottom of the world right now.”

He added, “The U.S. continues to have a bottom-tier performance in greenhouse gas emissions.”

AEI's Joel Schwartz thinks the emphasis on climate was undue and produced quite skewed results.

The U.S. scored 81 on the overall EPI, putting it 39th out of 149 countries. The U.S. scored worse than such environmental edens as Russia, Albania, Croatia, and the Dominican Republic, and barely edged out Cuba, Mexico, and Poland. That alone gives you an idea of the EPI’s tenuous relationship to the real environment. But let’s dig into the numbers a bit deeper to see how the Yale scientists played their game of let’s pretend.

Two words: climate change. Carbon dioxide emissions account for half of the Ecosystem Vitality score and 25 percent of the overall EPI score. The U.S. scored 56 out of 100 on climate change, and that is the main reason for America’s low overall EPI. If you look only at the Environmental Health index — in other words, the factors that directly affect people’s health — the U.S. scored 98.5 out of 100. In fact, virtually all the world’s wealthy countries scored above 95 on this measure.While the Yale researchers style their EPI as a valid measure of a country’s overall environmental performance, only one factor — greenhouse gas emissions — accounts for most of the variation in developed countries’ EPI scores.

Yale’s EPI is misleading in other ways. For example, ozone levels account for 3.75 percent of the overall EPI index score. But according to Yale’s report, the score was based on data for 2000 rather than current data. Ozone has dropped considerably in the U.S. since 2000. Fifty-four percent of the nation violated the federal eight-hour ozone standard in 2000. But the violation rate had dropped to 15 percent by the end of 2006. The average number of days per year exceeding the eight-hour standard declined 65 percent over the same period.

In any case, the ozone score isn’t even based on measured values, but on the output of a global atmospheric chemistry model whose predictions have little relationship to actual ozone levels across the country. U.S. air quality is among the best in the world. Nevertheless, in a New York Times story, one of the Yale researchers claimed that the U.S. “is at the bottom of the world right now” on regional smog.

The EPI’s air quality score also includes sulfur dioxide (SO2). But the score is based on SO2 emissions per unit of populated land (which doesn’t appear to be defined in the report), rather than on actual SO2 levels in the air. The U.S. scores poorly here (88 vs. 100 for most countries) even though U.S. SO2 levels are only a fraction of the federal health standard virtually everywhere in the U.S.

Joel Schwartz's colleagues Ken Green and Steve Hayward added their two cents here and here, respectively.

UPDATE: Whether or not the EPI's emphasis on climate change can be justified depends in large part on what the EPI purports to measure. As Tokyo Tom comments, "climate change scores tell us little about the health of a country's domestic environment." So, emphasizing climate change makes the EPI less useful as an indicator of environmental conditions within various countries. This is particularly so because the index does not even attempt to measure adaptation efforts.

If, however, the EPI is not intended to be used as a measure of environmental quality across nations, but as a measure of particular environmental outputs or the stringency of regulatory regimes, then the disproportionate emphasis might be justified. As structured, however, the EPI seems to be something of a hybrid, undermining the usefulness of the results as much more than a cudgel to use against U.S. policymakers for their failure to adopt more aggressive climate measures. Further, the EPI could still be subject to the criticism that its various climate measures are somewhat redundant, and ignore the impact of non-regulatory mitigation efforts.

On air quality, Joel Schwartz's critique is relevant for several reasons because the EPI is purporting to measure air quality insofar as it poses a threat to human health. Unless one believes that U.S. ambient air quality standards are grossly underprotective of human health, it is difficult to argue that U.S. air quality poses a significantly greater risk than that in other countries when most of the U.S. is meeting the relevant standards, as is the case with SO2. Further, the EPI's purported focus on human health makes the reliance on emissions and model projections inferior to measurements of actual ambient concentrations to which people are exposed. Further, as he notes, some of the data is quite out-of-date, lessening the EPI's value as an evaluation of current environmental conditions.

I have no idea how the United States would score if some of these concerns were addressed. These problems nonetheless provide ample reason for skepticism about the meaningfulness of the EPI rankings.

The Mitt Romney campaign has announced several additions to its Advisory Committee on The Constitution and The Courts, including several prominent lawyers who had previously supported Fred Thompson campaign. Among the former legal Fredheads to enlist in Team Romney include former Deputy Assistant Attorney General Victoria Toensing, Former Assistant Attorney General Rachel Brand, Former Assistant Attorney General Viet Dinh, Former Assistant Attorney General Charles Cooper, Former Assistant Attorney General Eileen O'Connor, and Former Deputy Assistant Attorney General Noel Franscisco, among others. It's an impressive list of additions to an already impressive roster of legal talent. Notably absent from the list, however, are any of the former Fredheads who contribute to this blog. As far as I am aware, we are all still uncommitted.

A reader asks:

I'm interested in finding some good libertarian fiction for my (almost) twelve year-old -- "libertarian" because I'd like her to get some exposure to those ideas, and "fiction" because that's what interests her. The problem is that I haven't read a lot of libertarian fiction, and I started when I was much older. Most of the stuff I'm familiar with has some fairly adult content.

Naturally, different people have different views about what's suitable for 12-year-olds, or for that matter what 12-year-olds are likely to find interesting. But even given this, I expect that many readers would like to hear suggestions on this score. Please post your recommendations in the comments, with whatever details you might like.

(paragraph break added):

[Anacharsis] laughed at [Solon] for imagining the dishonesty and covetousness of his countrymen could be restrained by written laws, which were like spiders' webs, and would catch, it is true, the weak and poor, but easily be broken by the mighty and rich.

To this Solon rejoined that men keep their promises when neither side can get anything by the breaking of them; and he would so fit his laws to the citizens, that all should understand it was more eligible to be just than to break the laws. But the event rather agreed with the conjecture of Anacharsis than Solon's hope.

Thanks to my colleague and former teacher Bill McGovern for the pointer.

A New York Times Ethicist column discusses this, but here's a more detailed account:

A student who wrote disparaging comments on an anonymous course evaluation now finds himself facing University sanctions.

Brian Beck, a landscape architecture major from Gordon, was found in violation of three University Code of Conduct regulations in a decision announced last week by University Judiciary. Beck was found in violation of the code due to:

• Disruption of the teaching evaluation process

• On grounds of multiplicity

• Harassment based on presumed knowledge of the associate professor's sexual orientation

Beck's violations stem from comments made on two course evaluations in Joseph Disponzio's History of the Built Environment course sequence.

On the first course evaluation, Beck was asked "What aspects of the course could use improvement or change?"

Beck wrote: "Joe Disponzio is a complete asshole. I hope he chokes on a dick, gets AIDS and dies. To hell with all gay teachers who are terrible with their jobs and try to fail students!" ...

[On the second course evaluation,] Beck answered the evaluation question "What were the most helpful/useful aspects of the course?" with "Joe Disponzio needs help with his issues dealing with homosexuality. Fags are not cool and neither are ney [sic] yorkers."

After comparing the two evaluations to exams from the class, Disponzio said he was able to identify the student he thought made the comments....

A letter was mailed to Beck's home address on Sept. 6 stating "it is alleged that Mr. Beck wrote threatening comments on course evaluations that were directed to a faculty member. Such comments indicated that he wanted the faculty member to die. Also the comments may have violated the University's anti-discrimination and harassment policy in that comments made may have been discriminatory regarding sexual orientation." ...

The University retained a handwriting document examiner to confirm the author of the evaluations. Roy Fenoff, a 2004 graduate of the University and forensic document examiner, was faxed the evaluations in question and Beck's class exams. He "concluded that the questioned writing was indeed authored by Brian Beck." ...

Beck's punishment includes writing a 1,200-word essay on how his remarks affect the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender community and interact with a greater intolerance of the campus LGBT community, a letter of apology to Disponzio including constructive criticisms of his teaching style, and meeting with Michael Shutt, assistant dean of students, to discuss completion of SafeSpace training or other programs deemed appropriate....

The student's comments are obviously appalling -- but so is the punishment for the student's speech. The statements are not, I think, constitutionally unprotected threats; sometimes expressing a hope that someone would die may be seen as an implicit threat that the speaker will kill the person, but that doesn't seem to be so here.

But in any event, the university doesn't even claim that the student is punished solely because of the alleged threat: It expressly says that part of the reason for the investigation (and, one can infer, the ultimate punishment) was the anti-gay viewpoint of the statements. That's a pretty clear violation of the First Amendment.

The loss of confidentiality is troubling, too. Students were apparently assured that their comments are confidential. ("According to the Franklin College evaluation Web site, 'the Web-based course evaluation application has been designed to encourage candor. Your identity will not be associated with any of your responses.'") And while a student can reasonably infer that there'd be an exception for comments that really are death threats or evidence of crime, I doubt that a reasonable student would have assumed that the promise would be lifted when the statements expressed disfavored viewpoints.

And of course all this will leave students guessing when else they will be identified (and punished) for their evaluations -- what if a student, for instance, faults a professor for belonging to a religious group that the student thinks is irrational or evil (Scientology, extremist Islam, fundamentalist Christianity, and the like)? What if a student accuses a professor of being a "feminazi" or a "male chauvinist," and the university chooses to interpret that as resting partly on the professor's sex as well as the professor's views.

Finally, a hypothetical: Say that instead of faulting the professor in a class evaluation, the student had publicly written "comments [that] may have been discriminatory regarding sexual orientation" about a professor in a newspaper article, or in a blog post? I take it that under the University of Georgia's view, writing such a newspaper article would lead to discipline, too, right?

Perhaps a university could distinguish targeted speech sent (especially repeatedly) to the insulted person alone, such as insulting phone calls or e-mails. (I have touched on this question in the workplace context here, and there is some First Amendment precedent that may support this.) But both the student evaluation and the hypothetical newspaper article are speech conveyed to others (future students or administrators as to the evaluation, current students and other readers as to the newspaper article), and are entitled to full First Amendment protection. The University of Georgia does not, however, seem willing to give them this protection.

Thanks to Joel Grossman for the pointer to the New York Times piece.

Apparently, a student editor was assigned to write about Philip Morris USA v. Williams, but thought this far too mundane a topic. Here's the first paragraph:

The history of the Fourteenth Amendment is one of hierarchy and capitalism. In the Amendment's first 139 years, courts have consistently used it to perpetuate dominant notions of class and culture--to maintain deeply rooted inequality and resist meaningful changes in the areas of poverty, race, and gender. While the Amendment's beautiful language and spirit could have been used to ensure equality and meaningful participation in all aspects of a civil community, its words have instead been employed as a tool for just the opposite. Last Term, in Philip Morris USA v. Williams, the Supreme Court used the Fourteenth Amendment to reaffirm and enrich procedural and substantive due process protections for corporations sued for punitive damages. This is the sad reality of a legal system and a culture that have often lacked the courage necessary to promote the practice of daily human life in a manner consistent with our values. But by reconceptualizing the kinds of harms that it addresses, we can transform the Amendment--now itself part of the machinery of cruel myth and illusion--into a tool for equality and justice.

And the last:

One small child dies of starvation every five seconds. That child is one of nearly ten million people who die every year because of hunger. It would be hard for us to imagine watching a child die. In fact, if it were happening in front of us, most of us would do everything in our power to stop it. We must understand and confront the powerful psychological forces that allow us to put the face of this child out of our minds when we interpret constitutional language that purports to bind us to thinking seriously about life and liberty. Yet we live with this world, and we live with this Amendment. And we violate it every five seconds.

The Supreme Court, 2006 Term Leading Cases I. Constitutional Law C. Due Process (121 Harv. L. Rev. 275 (Nov. 2007).

All Related Posts (on one page) | Some Related Posts:

- A Final Response To Ilya:

- Limited Government, Politics, and Judicial Review:

- What if The Public Doesn't Like Limited Government? A Response to Ilya:...

- The Supreme Court's Approval Ratings and the Legitimacy of Judicial Review:

- One Last Response to Ilya:

- Judicial Review, Democracy, and Legitimacy:...

- Conservative Legal Academics, McCain-Feingold, and "Judicial Restraint":

- Conservative Legal Academics and the Constitutionality of McCain-Feingold:

- Brad Smith on John McCain:

Although Orin and I differ fundamentally over judicial review, we are united in our willingness to spend a sleepless night debating it. In his latest post, Orin claims that judges should be severely constrained in overruling legislatures because the latter more fully represent "the consent of the governed":

Where Ilya and I differ, I think, is in the nature and importance of governmental legitimacy. I think the legitimacy of government is premised on the consent of the governed. Notions of legitimacy are complex, of course, and I don't want to oversimplify matters too much. But legislatively enacted laws generally deserve respect because they reflect a process involving wide participation of those who will be governed by them through their elected officials. In contrast, judges impose constitutional limitations on their own, either acting individually as trial judges or on panels of a handful of judges. I think the closer connection to the consent of the governed of legislative acts relative to judicial ones provides an important reason judges should be reluctant to latch on to fallible and contested theories that would lead them to invalidate lots of legislation.

I have many objections to the above, but will limit this post to the three most important ones. First, a high proportion of legislatively enacted laws do not in fact represent "the consent of the governed" in any meaningful sense because the vast majority of voters are ignorant about them - often not even knowing of their existence. Indeed, if we really want laws that reflect the informed consent of the governed, we should strictly limit the scope of legislative power so that the amount of legislation would be small enough for rationally ignorant voters to have at least a minimal knowledge of. I develop these points in much greater detail in this article.

Second, to the extent that "the consent of the governed" implies the actual support of the majority of the actual public, it turns out that judicial review has at least as much or more consent-based legitimacy as legislative power does. As political scientist Terri Jennings Peretti shows in her book on the subject, polling data consistently shows that the vast majority of Americans strongly support judicial review and that the Supreme Court generally enjoys a much higher approval rating than Congress despite the fact that it routinely invalidates a great many more laws than Orin probably considers justified. I don't claim that strong judicial review is desirable merely because the vast majority of the public approves of it. Their support could be the product of ignorance or miscalculation. However, consistently strong public approval does suggest that judicial power has at least as much "legitimacy" in Orin's sense of the term as legislative power. Quite possibly more.

Finally, I think Orin oversimplifies when he says that "judges impose constitutional limitations on their own, either acting individually as trial judges or on panels of a handful of judges." In reality, judges' decisions are constrained by a political appointment process, by limits on their ability to implement decisions at odds with the views of other political actors, and by a highly institutionalized system of precedent and legal culture that make it difficult for any one judge or small group of judges to make radical changes "on their own."

All Related Posts (on one page) | Some Related Posts:

- A Final Response To Ilya:

- Limited Government, Politics, and Judicial Review:

- What if The Public Doesn't Like Limited Government? A Response to Ilya:...

- One Last Response to Ilya:

- Judicial Review, Democracy, and Legitimacy:

- Human Imperfection and Governmental Legitimacy: ...

- Conservative Legal Academics, McCain-Feingold, and "Judicial Restraint":

- Conservative Legal Academics and the Constitutionality of McCain-Feingold:

- Brad Smith on John McCain:

Where Ilya and I differ, I think, is in the nature and importance of governmental legitimacy. I think the legitimacy of government is premised on the consent of the governed. Notions of legitimacy are complex, of course, and I don't want to oversimplify matters too much. But legislatively enacted laws generally deserve respect because they reflect a process involving wide participation of those who will be governed by them through their elected officials. In contrast, judges impose constitutional limitations on their own, either acting individually as trial judges or on panels of a handful of judges. I think the closer connection to the consent of the governed of legislative acts relative to judicial ones provides an important reason judges should be reluctant to latch on to fallible and contested theories that would lead them to invalidate lots of legislation.

All Related Posts (on one page) | Some Related Posts:

- A Final Response To Ilya:

- Limited Government, Politics, and Judicial Review:

- What if The Public Doesn't Like Limited Government? A Response to Ilya:...

- Judicial Review, Democracy, and Legitimacy:

- Human Imperfection and Governmental Legitimacy:

- Human Imperfection, Bias, and Theories of Constitutional Law:...

- Conservative Legal Academics, McCain-Feingold, and "Judicial Restraint":

- Conservative Legal Academics and the Constitutionality of McCain-Feingold:

- Brad Smith on John McCain:

In Russian fairy tales, some powerful person sometimes sends the hero off on a quest by saying, "Go there, I don't know where, bring that, I don't know what." Somehow the hero manages, but that's because it's a fairy tale.

I've been reminded of this by reading the accounts of the Brandeis administration's finding that Prof. Donald Hindley was guilty of "racial harassment" because he said ... well, the administration isn't saying exactly what he supposedly said. Press accounts agree that it involves (at least) the use of the word "wetback," but the context is far from clear. Since my earlier post, I've looked a bit at the coverage in university newspapers, and here's what I see:

Hindley defended his discussion of the term, saying he had used it to describe racism of a certain historical period. Throughout American history, he said, "When Mexicans come north as illegal immigrants, we call them wetbacks." ...

"[Administrator Jesse Simone, who was questioning Hindley,] said, 'Did you use the word wetback?' Well, I teach Latin American politics and I'm currently teaching Mexican politics, and of course I use the word wetbacks, [but] not in any derogatory sense," Hindley said ....

Hindley said Simone also asked if he had referred to "young, white males having contact with women of color," which he said he had.

2. From the same article, a statement by Lily Adams, a student of Hindley's who defended him:

Adams also denied Hindley had used the term in an offensive context. "If he had made comments that were legitimately racist, the whole class would have complained,' she said, adding, It was never him saying, 'This is what I call them,' or, 'This is an appropriate term.'"

3. From an article in a different student newspaper (thanks to Prof. Margaret Soltan (University Diaries) for the pointer), here's the student's account:

Jane [the complaining student's pseudonym] explained that her complaints dealt with alleged insensitivity by Hindley to the issues in his class, including usage of the terms "mi petite negrita" and "wetbacks."

"The thing that pushed me over the edge was a story about a Brandeis student that he had who came from an elite Mexican family. He said, 'he came here and he paid his way.... but when he came back here, his back was still wet,'" said Jane. "That was the day I came to my professor and said, 'this is crazy.' These flippant remarks, he doesn't see that they affect other people — it's a joke, to him."

Jane also makes other allegations (and the article also notes that "[d]espite her complaints, Jane said she may take another course with Hindley, because 'I won't have to do work'").

4. From the same article that quotes Jane, a quote from student Ramon de Jesus, and a respone from Jane:

"I think that the allegations which are being made against Hindley are being done so by someone who is taking things out of context. It is interesting that the person whom you interviewed almost brushes context off as if it does not matter, when in fact, it is extremely important," said Ramon de Jesus '08.

"If context were not important, everything anyone ever said could be misconstrued one way or another. As a student of color who has taken both Latin American Politics classes with Hindley, I can honestly say that the man is not racist."

He added "I'm not in a Hindley class currently, but if given the opportunity I would sign up for another one."

Regarding Hindley's statements, "sure there is context, but it should be treated gently, especially with students from so many different cultures," said Jane.

"You have Latin American students, Mexican students ... there are Jewish students, homosexual students, black students — you're just running the gamut in this classroom. I would think that would call for extra sensitivity, but I guess he doesn't think so," she said.

Now the Brandeis administration obviously thinks that what Hindley said was impermissible, and indeed "racial harassment." It thinks that professors shouldn't say such things. But what is it that they shouldn't say?

If Brandeis thinks Hindley said "wetback" in the context as he describes it, then I take it that Brandeis's view is that professors should never use such terms in class — perhaps not even in direct quotes, and certainly not (as Hindley says he did) in made-up quotes characterizing what people think. If Brandeis thinks Hindley said "wetback" as part of a humorous aside, then I take it that Brandeis's view is that professors shouldn't say such things in class in a humorous context. If Brandeis thinks Hindley said "wetback" in a way that endorsed the view that illegal immigrants (or illegal immigrants from Mexico) are bad people, then I take it that Brandeis's view is that professors shouldn't express such views in class using pejorative terms. Or perhaps Brandeis thinks any condemnation of illegal immigrants (or illegal immigrants from Mexico), whether or not using the term "wetback" (a term that the administration didn't even mention in any of the documents I've seen from it), is a view professors shouldn't express in class.

But how on earth is a professor to know what he shouldn't be saying when the University doesn't even reveal what led to this high-profile discipline? And how are faculty members — and students and alumni and others — to know whether the University's action invades academic freedom, promotes good teaching, or whatever else without knowing what it is that Hindley supposedly said?

Nor is the University's explanation for its silence remotely justifiable. As best I can tell from the accounts, the University's argument is that it can't describe what specifically was said because it needs to protect the student's confidentiality — but if this was supposedly said in open class, why would revealing the statement jeopardize the student's confidentiality? (The article that quotes Jane quotes her as saying that she "came to [her] professor and said, 'this is crazy'"; presumably she means someone other than Hindley when she says "my professor," but if she did tell him, then I'm still more baffled by how there could be any risk to the student's confidentiality here.)

Finally, I realize that the administration might conclude that it can't specifically identify exactly what was said, but that it can figure out the general gist sufficiently to conclude that a racial harassment finding is warranted. Fine — but tell us what that gist is, so that professors can know what they shouldn't say, and so that others can evaluate the administration's actions. But the administration didn't do even that.

Related Posts (on one page):

- ACLU of Massachusetts Condemns Brandeis University

- Better Not Denigrate Religions / Disabilities / Veteran Status / Sexual Orientation / Etc. at Your University:

- Calling Brandeis Professors and Students:

- Saying "Jehovah" at Brandeis?

- Don't Say This, I Won't Tell You What:

- Brandeis University Trying To Discipline Professor

Orin's most recent post cuts through some of the fog generated by previous exchanges and gets to the heart of what he correctly characterizes as a big disagreement between our respective theories of constitutional interpretation:

For my part, I tend to be highly skeptical of grand constitutional theories that would lead courts to strike down lots of laws. Human nature is fallible and highly imperfect: it's only natural to embrace theories that reach results you like while being deeply convinced that you are following principle and the other guy is being result-oriented. Thus, libertarians are drawn to libertarian theories, progressives are drawn to progressive theories, etc. In the end, it just so happens that everyone seems to have a Grand Theory of the True Constitution by which a lot of laws they don't like end up being unconstitutional.

What I find interesting about my disagreements with Orin is that I agree with his premises but disagree with the conclusions he draws from them. Here, I agree that "human nature is fallible and highly imperfect" and that people tend to "embrace theories that reach results [they] like." But I disagree that this means we should be unusually skeptical about theories that "would lead courts to strike down lots of laws." If human nature is fallible and imperfect, that applies to the nature of legislators and voters no less than to that of judges. If ideological bias affects people's preferences about constitutional theory, that applies to theories that would lead courts to uphold lots of laws no less than to those what would lead them strike lots of laws down. People who like the outcomes of the political process will be biased in favor of theories that lead courts to uphold most laws no less than those who dislike those outcomes will have a bias the other way. And all of this applies to "non-grand" theories of constitutional interpretation no less than to "grand" ones.

Thus, the existence of human imperfection and bias does not justify judicial deference to legislative power. If anything, it justifies at least some degree of aggressive judicial review. After all, if humans are biased, fallible and imperfect, we should not allow the biased, fallible, and imperfect humans who populate the legislature and the electorate to be the sole judges of the scope of their constitutional authority.

All Related Posts (on one page) | Some Related Posts:

- A Final Response To Ilya:

- Limited Government, Politics, and Judicial Review:

- What if The Public Doesn't Like Limited Government? A Response to Ilya:...

- Human Imperfection and Governmental Legitimacy:

- Human Imperfection, Bias, and Theories of Constitutional Law:

- Legal Divide Rocks the Volokh Conspiracy!:...

- Conservative Legal Academics, McCain-Feingold, and "Judicial Restraint":

- Conservative Legal Academics and the Constitutionality of McCain-Feingold:

- Brad Smith on John McCain:

For my part, I tend to be highly skeptical of grand constitutional theories that would lead courts to strike down lots of laws. Human nature is fallible and highly imperfect: it's only natural to embrace theories that reach results you like while being deeply convinced that you are following principle and the other guy is being result-oriented. Thus, libertarians are drawn to libertarian theories, progressives are drawn to progressive theories, etc. In the end, it just so happens that everyone seems to have a Grand Theory of the True Constitution by which a lot of laws they don't like end up being unconstitutional. And yet no seems able to convince anyone else that their theories of constitutional interpretation are wrong. I fear that in result, if not in intention, such theories too often become politics by other means.

All Related Posts (on one page) | Some Related Posts:

- A Final Response To Ilya:

- Limited Government, Politics, and Judicial Review:

- What if The Public Doesn't Like Limited Government? A Response to Ilya:...

- Human Imperfection, Bias, and Theories of Constitutional Law:

- Legal Divide Rocks the Volokh Conspiracy!:

- Conservative Legal Academics, McCain-Feingold, and "Judicial Restraint":

- Conservative Legal Academics and the Constitutionality of McCain-Feingold:

- Brad Smith on John McCain:

Wednesday, January 23, 2008

I have to disagree with co-blogger Orin Kerr's claim that "conservative" principles of "judicial restraint" should "lead a truly consistent conservative judge to be inclined to uphold McCain Feingold." Judicial restraint is not necessarily the same thing as upholding whatever statutes legislatures should happen to enact [update: this is poor wording - I should have said "not necessarily the same thing as granting a strong presumption of constitutionality to whatever statutes legislatures happen to enact"]. Rather, a properly restrained judge should vote to strike down statutes whenever they violate the text and original meaning of the Constitution, without giving the legislature any special deference. Failing to strike down an unconstitutional statute is no less a departure from the proper judicial function than wrongly striking down a statute that is constitutionally permissible. In an age where government - especially the federal government - has grown far beyond its constitutional bounds, striking down unconstitutional statutes may well be a more urgent judicial priority than upholding permissible ones.

As I discussed in more detail in this post, most conservative - and even more so libertarian - legal scholars recognize the need to strike down unconstitutional statutes and have long criticized the Supreme Court for being excessively deferential to legislatures in areas such as federalism and property rights. A few conservative legal academics - such as Robert Bork and Lino Graglia - do hold the view that judicial review should be severely truncated across the board. But that view has long been a minority one among nonliberal legal academics. Brad Smith, the scholar whose post Orin criticizes, is not a conservative but a libertarian. Libertarian academics, of course, have been even stronger supporters of judicial review than conservative ones.

Orin hints at some of the above when he notes that conservatives support "strict constructionist" jurisprudence. To the extent that "strict constructionism" is a synonym for textualism and originalism, it does not imply broad deference to legislative enactments. To the contrary, it requires judges to strike down as many as possible of the large and growing number of modern statutes that have expanded legislative power beyond the bounds of the Constitutional text and original meaning.

None of this settles the issue of McCain-Feingold's constitutionality. It does, however, undercut the argument that consistency requires conservatives to oppose judicial invalidation of this statute because this outcome is dictated by "conservative" principles of "judicial restraint" that allegedly require broad judicial deference to anything enacted through the legislative process.

UPDATE: In the comments, Orin suggests that I misinterpreted his original post. Orin is the best judge of what he meant to say, so I defer to him on that and apologize for misunderstanding his meaning. I will, say, however, that it's not clear how his argument - as elucidated in his comment - proves that conservatives who believe McCain-Feingold to be unconstitutional are "inconsistent." If "conservative" principles of "judicial restraint" do not require broad deference to Congress' enactments, then I don't see why they should "lead a truly consistent conservative judge to be inclined to uphold McCain Feingold."

All Related Posts (on one page) | Some Related Posts:

- A Final Response To Ilya:

- Limited Government, Politics, and Judicial Review:

- What if The Public Doesn't Like Limited Government? A Response to Ilya:...

- Legal Divide Rocks the Volokh Conspiracy!:

- Conservative Legal Academics, McCain-Feingold, and "Judicial Restraint":

- Conservative Legal Academics and the Constitutionality of McCain-Feingold:

- Brad Smith on John McCain:

Perhaps a foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds, but I would think that this methodology as applied to campaign finance would lead a truly consistent conservative judge to be inclined to uphold McCain Feingold under old fashioned Thayeresque principles of judicial restraint, regardless of the merits of such legislation as a matter of policy. Of course, conservative legal thought comes in many diverse strands, so of course it's not the only result a conservative judge could reach. But if you believe that legal principles should be applied consistently, without regard to which party's ox is being gored, I would think this would be a strong and principled conservative approach.

All Related Posts (on one page) | Some Related Posts:

- A Final Response To Ilya:

- Limited Government, Politics, and Judicial Review:

- What if The Public Doesn't Like Limited Government? A Response to Ilya:...

- Conservative Legal Academics, McCain-Feingold, and "Judicial Restraint":

- Conservative Legal Academics and the Constitutionality of McCain-Feingold:

- Brad Smith on John McCain:

Capital University law prof, former FEC Commissioner, and Romney supporter Brad Smith has this to say about why so few conservative law professors have jumped on the McCain bandwagon:

I think that conservative law professors, who as I say, probably care more about the issue of judges and are on average in a better position to consider the candidates on this particular issue than are most other conservative activists, don't like what they see in McCain. Some of it is the problem of McCain-Feingold. McCain is likely to make support for McCain-Feingold - an issue he has said is "of transcendent importance" to him - a litmus test for judges. It is very hard, however, to find judicial candidates who think McCain-Feingold is constitutional yet who are also are anti-Roe v. Wade and generally respectful of the Constitution. For anyone with a coherent judicial philosophy of federalism and limited government, the two just don't go together. When McCain says he wants to appoint justices like Thomas and Scalia, we must consider that Thomas and Scalia would overrule all of McCain-Feingold, indeed all pre-existing campaign finance law except perhaps some disclosure. It is almost impossible to believe that Senator McCain would appoint Thomas or Scalia to the bench, let alone the Supreme Court.

Of course, there was a time when conservatives were significantly less sympathetic to a broad interpretation of the the First Amendment than were liberals. Perhaps President McCain will regress conservatives to the historical mean.

All Related Posts (on one page) | Some Related Posts:

- A Final Response To Ilya:

- Limited Government, Politics, and Judicial Review:

- What if The Public Doesn't Like Limited Government? A Response to Ilya:...

- Conservative Legal Academics, McCain-Feingold, and "Judicial Restraint":

- Conservative Legal Academics and the Constitutionality of McCain-Feingold:

- Brad Smith on John McCain:

"Their attorneys blamed their conviction on the numerous times prosecutors used al Qaeda and its leader Obama bin Laden in trial. Cooke also allowed jurors to see a videotape of Obama bin Laden." A big whoops!, from the Daily Business Review (South Florida), caught by David Markus. Yes, I know, such gaffes had been heard before, but it's a little worse in written text.

and that apparently includes all its archives. Cool. Extra bonus: The current issue has Virginia Postrel's Substance-of-Style-ish piece on fonts, plus an interview with the director of the documentary Helvetica.

Johan Richter writes the following query to me:

As the primary elections are coming up is is interesting to note that so many of the contenders are lawyers, something that is also true of the members of Congress, where I believe half are lawyers. Why are so many US politicians lawyers? It seems odd considering that A) Legal training seems unnecessary for performing the main job of a politician, regardless of whether one takes that to be courting public opinion or governing the country. And there is hardly any deficit of lawyers in Washington to ask for advice if legal knowledge turns out to be needed. B) Being a lawyer isn’t very prestigious as far as I know. Being a military, doctor, police officer, businessman or perhaps even a academic would surely be regarded by many voters as more respectable professions than being a lawyer. C) Other countries don’t have nearly the same over-representation of lawyers in their parliaments as the US does.

I thought Google would yield a paper on this question but I can't find it. My guess is that lawyers are good at fundraising and good at developing personal contacts. This helps explain why fewer politicians are lawyers in many other countries; money is more important in American politics. A lawyer also has greater chance to exhibit the qualities that would signal success in politics, such as the ability to persuade and the ability to speak well on one's feet. Not to mention that many lawyers have ambition.

My wife Natasha, who is a lawyer, adds that law generates an outflux of people to many other fields, not just politics. There is also a path-dependence effect, by which a previous presence of politicians in law breeds the same for the future. What else do you all know about this?

A similar version of this post can be found at www.marginalrevolution.com.

This Friday, I will be speaking on the Case Western Reserve University School of Law conference on "Corporations and their Communities" (schedule available here). My presentation will be on the use of eminent domain and "economic development" takings to try to entice corporations to stay in a given community or come in. I will discuss why I think using eminent domain for such purposes is generally undesirable, not only from the standpoint of fairness to property owners but even with respect to the goal promoting longterm economic development in the community. Some of the points I plan to make are based on this article. I will also briefly discuss the extensive legislative backlash against economic development takings in the in the wake of Kelo v. City of New London (analyzed in this paper, on which I will soone be posting a major revision).

If you are a VC reader in the Cleveland area or otherwise interested in these issues, I hope you will drop by and check out the panel. The conference also includes many well-known scholars, including co-conspirator and Case Western professor Jonathan Adler.

for saying (in a Latin American politics class) that "Mexican migrants in the United States are sometimes referred to pejoratively as 'wetbacks'"? That's what the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education reports, though pointing out that Brandeis hasn't even explicitly said exactly what speech of his was found to be "racial[ly] harass[ing]." FIRE (which I've found to be consistently factually credible) also points to Brandeis faculty committees that strongly condemn the procedures that the university has used, and argue — quite correctly, if the facts are as they are described — that this is a serious violation of academic freedom.

I should note that I'm not as hostile as the faculty committees are to the administration's decision to place a monitor in the professor's class. It seems to me that people who pay one's salary to teach are entitled to know what one is teaching. And if the monitor was looking for, say, targeted personal insults of individual students (if that were the allegation), that would be a plausible thing for the monitor to do (though my view is that recording the class would be a less disruptive way of doing that). Likewise, if there were simply reports that the professor was teaching in a confusing and ineffective way, the administration should be entitled to look in on the classes and see whether they can offer the professor constructive advice, or perhaps evaluate the teaching to see if the professor falls below minimum tenure standards (or perhaps should be reassigned to teaching some other class in which he does better).

The trouble is that the administration seems to be using a vague and potentially extremely broad definition of what the professor is not supposed to be saying — it's not just the monitoring, but monitoring coupled with (1) the threat of punishment for speech for which a professor ought not be punished, (2) a finding of racial harassment based on the earlier statements, and (3) seemingly serious procedural failings in the process the administration has used. Looks like very bad stuff, given the facts reported on the FIRE site and the documents to which it links.

UPDATE: Prof. Margaret Soltan (at George Washington University) blogged several weeks ago about the controversy (and also here); I haven't read all the details, but I thought I'd forward the link. Thanks to reader Cactus Jack for the pointer.

FURTHER UPDATE: I have more about the facts, and the problems with Brandeis' actions, here.

Related Posts (on one page):

- ACLU of Massachusetts Condemns Brandeis University

- Better Not Denigrate Religions / Disabilities / Veteran Status / Sexual Orientation / Etc. at Your University:

- Calling Brandeis Professors and Students:

- Saying "Jehovah" at Brandeis?

- Don't Say This, I Won't Tell You What:

- Brandeis University Trying To Discipline Professor

A "study" out of Columbia Law School, trumpeted in a law school press release, boldly states that based on LSAC data African American and Mexican American matriculation in law schools declined between 1992 and 2005, even though more law school slots are available overall due to the opening of new law schools.

There are some real oddities with this study. First, the LSAC apparently changed its data collection methods in 2000, and an LSAC page (go to the "Data" link) warns that data starting that year is not comparable to earlier data, which would seem to make the entire exercise of comparing data from 1992 to data in 2005 moot.

Second, that LSAC page shows 2,980 African American and 620 Mexican American matriculants to law school in 2005, consistent with the Columbia study. But a different LSAC web page shows a steady increase in Mexican American first-year students to 866, up from 807 in 1992 (and 586 in 1986), and a slight decrease in African American first-year students from 3,303 in 1992 (and 2,156 in 1986) to 3,132 in 2005 (rebounding to 3,516 in 2006). Similarly, this page shows Puerto Rican matriculants holding steady at just over 200, while this page shows a steep increase to 780.

Both pages show a very substantial increase in the number of "other Hispanics," to over 2,000--conveniently left out of the Columbia study--but again the exact numbers differ. And given that Mexican American and Puerto Ricans compose about three-quarters of the Hispanic population of the United States, can it really be that their numbers in law school are dwarfed by "other Hispanics"? Perhaps some Mexican Americans are checking off "Hispanic/Latino" instead of "Chicano/Mexican American"?

Thanks to my colleague Michael Krauss for the pointer.

This afternoon, GW law professor (and Concurring Opinions blogger) Daniel Solove will be delivering a lecture on "“The Future of Reputation: Gossip, Rumor, and Privacy on the Internet" at the Case Western Reserve University School of Law. The talk, which is sponsored by the Center for Law, Technology, and the Arts, will build upon the themes of Solove's recent book of the same name. Here's a brief description of the talk:

What information about you is available on the Internet? What if it’s wrong, humiliating, or true but regrettable? Will it ever go away?

Teeming with chatrooms, online discussion groups, and blogs, the Internet offers previously unimagined opportunities for personal expression and communication. But there’s a dark side to the story. A trail of information fragments about us is forever preserved on the Internet: a chronicle of our private lives—often of dubious reliability and sometimes totally false—instantly accessible to friends, strangers, dates, employers, neighbors, relatives, and anyone else who cares to look.

Focusing on blogs, Internet communities, cyber mobs, and other current trends, Professor Solove will explore the profound implications of the online collision between free speech and privacy as he offers a fascinating account of how the Internet is transforming gossip, the way we shame others, and our ability to protect our own reputations.

Longstanding notions of privacy need review, and unless we establish a balance among privacy, free speech, and anonymity, we may discover that the freedom of the Internet makes us less free.

The event will be webcast live. Details here.

The Washington Post writes,

Despite the steady drop in abortions across the United States in the three decades since the Supreme Court legalized the procedure in 1973 in the case of Roe v. Wade, a new generation of activists is taking up the cause with conviction and sophistication.

Why "despite"? Whether you agree with anti-abortion activists or not, they generally take the view that abortion is a grievous wrong. A steady drop in abortions doesn't make the remaining abortions any less wrong.

You'd think that a new generation of activists would still be energized to "tak[e] up the cause with conviction and sophistication" even if they think there are only several hundred thousands fetal lives to be saved each year rather than over a million. Perhaps the steady drop might even energize them into thinking that women's minds can be changed about the procedure; but in any case, I don't see why it would make them less interested in changing still more minds (and changing the law). The "despite" strikes me as a signal that the author and the editor are for some reason missing this pretty important fact about the motivations of the very people they're writing about.

(If Roe had actually decreased the total number of abortions per year, then it might be surprising that people would want to try to overturn it, though even then people might still actively urge women not to get abortions. But the total number of legal abortions plus illegal abortions increased following Roe, as one might expect.)

Thanks to OpinionJournal's Best of the Web, which has more.

UPDATE: An exchange with commenter Rich B. led me to look at some more data, which suggest the possibility that the aggregate legal and illegal abortion rate today is roughly the same as it was just before Roe; see here. I'm not positive that this is so, especially since the Alan Guttmacher Institute numbers are quite a bit higher from the CDC numbers, and since the Guttmacher Institute itself -- a defender of abortion rights -- reports that the current abortion rate is the lowest since 1974, not since 1972. Likewise, this file from Guttmacher reports a higher rate in 2005 than in 1973, without any qualifiers indicating that it's reporting only illegal abortions.

Nonetheless, even if the abortion rate is the same now as right before Roe, the shape of the curve is pretty clear: A huge spike in overall legal plus illegal abortions in the 1970s, followed by a slow but fairly steady and substantial decline since about 1980 (which is what I take the Post is somewhat confusingly describing as "the steady drop in abortions across the United States in the three decades since the Supreme Court legalized the procedure in 1973"). The spike is consistent with the view that legalization -- both before Roe in some states, and after Roe in all states -- increased the number of abortions; the decline seems most plausibly explained by changing social or economic conditions, quite possibly including increased public anti-abortion advocacy. It's of course possible that Roe was completely irrelevant, and that the spike was entirely due to other causes; it just doesn't seem very likely to me, and it certainly doesn't seem like the only plausible or even the most plausible explanation from the perspective of those who condemn abortion.

Thus, to return to the point I mentioned, even if the total abortion rate is roughly what it was right before Roe, it makes perfect sense that "a new generation of activists is taking up the cause with conviction and sophistication."

Tuesday, January 22, 2008

Why does this matter, you wonder? Well, there are two reasons. First, I would think agents would have an incentive to use this catch and release tactic in some settings if it is permitted. For example, imagine an FBI agent is investigating a suspect for narcotics smuggling. He can just stop the suspect for driving 36 in a 35, arrest him for speeding under state law, and search him for evidence or drugs. If no evidence is discovered in the search, then the officers will just let the suspect go and plan on getting him next time. Under the state's theory, as I understand it, this is perfectly okay: The arrest is based on probable cause, and the search is incident to a valid arrest because the arrest is based on probable cause. On the other hand, if the FBI agent uncovers evidence of a federal offense during the search incident to arrest, he can either bring in the target into federal court on the basis of the new evidence or let him go and keep the evidence for later.

The second reason is that the "catch and release" tactic would seem to be relevant under Justice Souter's reasoning in Atwater v. Lago Vista. Justice Souter invoked the notion that arrest powers would be subject to political checks by the sovereign that enacted the relevant law:

So far as [arrests for minor offenses] might be thought to pose a threat to the probable-cause requirement, anyone arrested for a crime without formal process, whether for felony or misdemeanor, is entitled to a magistrate’s review of probable cause within 48 hours, County of Riverside v. McLaughlin, 500 U.S., at 55—58, and there is no reason to think the procedure in this case atypical in giving the suspect a prompt opportunity to request release, see Tex. Tran. Code Ann. §543.002 (1999) (persons arrested for traffic offenses to be taken “immediately” before a magistrate). Many jurisdictions, moreover, have chosen to impose more restrictive safeguards through statutes limiting warrantless arrests for minor offenses. . . . It is, in fact, only natural that States should resort to this sort of legislative regulation, for, as Atwater’s own amici emphasize, it is in the interest of the police to limit petty-offense arrests, which carry costs that are simply too great to incur without good reason. See Brief for Institute on Criminal Justice at the University of Minnesota Law School and Eleven Leading Experts on Law Enforcement and Corrections Administration and Policy as Amici Curiae 11 (the use of custodial arrests for minor offenses “[a]ctually [c]ontradicts [l]aw [e]nforcement [i]nterests”). . . .If agents are permitted to use a catch-and-release tactic, using state criminal law and not being limited by any state law restrictions, then these checks would seem to go away. First, there would be no check by a magistrate, because the federal agents would never bring in the target. Second, the state law restrictions wouldn't apply to the federal officers. Third, there would be no great costs of the arrests, as there would be no cases processed in court and the suspect would be set free. And fourth, there would be little political check, as the agent isn't even an official of the state that enacted the crime (and good luck complaining to the FBI about your fully-constitutional-but-really-annoying temporary arrest).

The upshot of all these influences, combined with the good sense (and, failing that, the political accountability) of most local lawmakers and law-enforcement officials, is a dearth of horribles demanding redress.

Off the top of my head, I gather that this would be okay under the state's theory of the case. After all, the agent would have probable cause to believe a crime had been committed, and that's enough. Am I wrong about this implication of the state's theory? Or perhaps Virginia (or the United States) would say that probable cause is enough only if the arresting officer is an agent of the sovereign that has prohibited the conduct?

UPDATE: I substantially amended the post shortly after posting it. In ligt of that, I have deleted a few comments that addressed a part of the post that was only up for a few minutes. My apologies for the lost effort on the part of those commenters.

Related Posts (on one page):

- Virginia v. Moore and the Changing Role of the Fourth Amendment:

- Supreme Court Hands Down Virginia v. Moore:

- "Catch and Release" Tactics and Virginia v. Moore:

- Oral Argument in Virginia v. Moore:

- Why United States v. Di Re Clearly Was Not A Case on the Federal Supervisory Power:

- Why the Defendant Should Win in Virginia v. Moore:

Tom Brady generally has vastly better fashion sense than I do. However, he apparently is wearing a very similar orthopedic boot to the one that I have. I'm wearing it because I had surgery for a broken ankle seven weeks ago and am not yet allowed to walk without one. Brady's injury is probably an ankle sprain or other relatively mild problem. If it were a fracture like mine, he would not be allowed to walk at all right now, and certainly not without the orthopedic boot (which he was spotted doing later the same day).

However, just in case Brady really is unable to play in the Super Bowl, I'd like to let the Patriots know that my boot comes off Thursday, and I've thrown almost as many passes this season as backup QB Matt Cassel. I'd be more than happy to take a few snaps for my favorite NFL team, so long as the Pats offensive line keeps Michael Strahan & Co. as far away from me as possible:).

You can watch my discussion of Boucher here (about 5 minutes long), and listen to my podcast on Moore here (about 13 minutes long).

I hadn't known this -- it turns out that the New Jersey Constitution of 1776 allowed all heads of households "worth fifty pounds clear estate" to vote in state elections, and therefore in elections for the federal House of Representatives. This didn't include married women, but it did include widows and adult unmarried women; and women did vote under this constitution, until the franchise was restricted to men in 1807.

There's a pretty thorough article on this, though available online only to JSTOR subscribers: Judith Apter Klinghoffer & Lois Elkis, "The Petticoat Electors": Women's Suffrage in New Jersey, 1776-1807, 12 J. Early Rep 159 (1992). Thanks to Prof. Rob Natelson for the information. Wikipedia also reports that a short-lived Corsican Republic (1755-69) provided for women's suffrage as well.

I haven't been watching this PBS documentary series (mostly because I don't watch t.v.), but a q & a with the writer/director raises a question. He writes, "Jewish Americans are probably the most liberal of any white ethnic group, and that liberalism dates from this deep attachment to F.D.R., the New Deal and the liberal principles for which both stood."

Hmm. My understanding of American Jewish history is rather different. As I understand it, many Eastern European Jews brought labor radicalism and socialism with them to America, and a substantial fraction, perhaps as much as 1/3, of American Jews (which would have included my own maternal grandfather and great-grandfather) identified themselves as socialists in 1932, before F.D.R.'s presidency could have had any impact on them. If anything, F.D.R. probably made American Jews less liberal (in the American political sense) by weaning many of them away from socialism and other forms of radicalism and into New Deal interest group liberalism, though he did win Jews' loyalty to the Democratic Party.

If we have any readers who are experts in American Jewish history or sociology, perhaps they will chime in.

On another topic, why is it a "darker corner of Jewish history" that "Jews owned many of the sweatshops [otherwise known as small, poorly capitalized factories] on the Lower East Side"? Is there some evidence that "sweatshop" owners made super-competitive profits because they had monopoly power or coerced their workers? That they failed to pay agreed-upon wages? That they received special favors from political connections? Am I the only one who has read The Rise of David Levinsky and wondered why the title character was considered a heinous villain in his day?

CBC News reports this; the lawyer is a Mobina Jaffer, member of the Canadian Senate. Nor does this seem like a timekeeping glitch, or some unusual accounting system agreed on with the client:

Liberal Senator Mobina Jaffer is under investigation by the Law Society of British Columbia for allegedly overbilling one of her legal clients, including charging for 30 hours of work in a single day, CBC News has learned....

Jaffer has been called before the law society to account for more than $6 million in legal bills charged to her former client, a Catholic missionary order known as the Oblates of Mary Immaculate....

The Oblates, whose B.C. headquarters are based in New Westminster, fired Jaffer and her son, Azool Jaffer-Jeraj, three years ago after receiving bills of $6.7 million. They had hired the Jaffers to defend them against dozens of claims of abuse in residential schools....

The Jaffers settled the lawsuit out of court in December; however, the law society said the case still requires an investigation....

The accounts obtained by the CBC also showed that Jaffer's son once billed for 32.4 hours in a day, at the end of a week in which he claimed an average of 20 hours of work a day....

[B]efore settling with the Oblates, both Jaffer and her son were examined under oath. Jaffer said then that billing for more than 24 hours a day was "an error." ...

Of course, these are Canadian hours, which at the time amounted to only 70% of an American hour.

So holds the Eighth Circuit, in my view quite rightly, given the Court's abortion rights caselaw. Prisoners understandably have to lose plenty of rights, whether because of prison security needs or because the loss of the right is part of the punishment. But accepting (as the Eighth Circuit must) that the Court has held that women have the right to choose an abortion, there's no substantial basis for restricting those rights this way; the Circuit's fairly detailed analysis of the state's various arguments strikes me as quite persuasive.

[a]ny claim arising in respect of the assessment or collection of any tax or customs duty, or the detention of any goods, merchandise, or other property by any officer of customs or excise or any other law enforcement officer, except that the provisions of this chapter and section 1346 (b) of this title apply to any claim based on injury or loss of goods, merchandise, or other property, while in the possession of any officer of customs or excise or any other law enforcement officer, if—The question in the case is whether the reference to "any other law enforcement officer" is implicitly limited to other law enforcement officers acting in the assessment or collection of a tax or customs duty, or whether it means any other law enforcement officer acting generally. Justice Thomas argues the latter; Justice Kennedy argues the former.

(1) the property was seized for the purpose of forfeiture under any provision of Federal law providing for the forfeiture of property other than as a sentence imposed upon conviction of a criminal offense;

(2) the interest of the claimant was not forfeited;

(3) the interest of the claimant was not remitted or mitigated (if the property was subject to forfeiture); and

(4) the claimant was not convicted of a crime for which the interest of the claimant in the property was subject to forfeiture under a Federal criminal forfeiture law.

Based on a quick skim, I'm not sure which side is more persuasive. On one hand, Justice Thomas is right that the statute on its face says that it applies to detention by "any law other law enforcement officer," a very broad phrase. On the other hand, Justice Kennedy is right that this would be a relatively weird way to make the point that all detentions by law enforcement officers are excluded. Based on a very quick read, it seems like a coin toss as to which side is more persuasive -- or at least a matter requiring a lot more study of the statutory scheme than a casual read would allow.

Reading over the opinions, I'm a little surprised that the litigants and the Justices apparently thought it obvious that prison officials count as "law enforcement officers." In my experience, prison officials are not generally considered to be "law enforcement" officers, as their role is running prisons rather than enforcing the law through the investigation and prosecution of criminal activity. But maybe it's clear in the statutory scheme that prison officials are law enforcement officers -- I don't know enough about the FTCA to say.

Finally, I thought the beginning of Justice Kennedy's dissent was a bit overdone. I don't see anything in Justice Thomas's opinion that suggests that the Court has now adopted "an analytic framework" of statutory interpretation that "become[s] binding on the federal courts." Rather, this case struck me as just a relatively common interpretive exercise trying to make sense of a rather awkwardly written statute.

Related Posts (on one page):

- Ali v. Federal Bureau of Prisons:

- Ruth "Swing Vote" Ginsburg?:

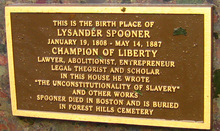

Here is a photo of the monument at his birthplace in Athol, Massachusetts:

Here is the apartment house in which he died:

Here is the monument on his grave at Forest Hills Cemetery in Boston:

Happy Birthday Lysander!

Sam Karnick's blog "The American Culture" quotes my positive reaction to the EU's pro-privacy stance on search engines collecting IP addresses. The EU position is contrary to Google's practices. In some European countries, Google's search engine dominance is even greater than in the United States.