|

Saturday, December 27, 2008

Have a lousy Christmas, with a note on banking regulation.

Some people are offended if you say “happy holidays” and others are offended if you say “merry Christmas.” Some people are offended if you are offended by one greeting or another, and some people are offended by efforts to explain why some people are offended when other people are offended by one greeting or the other. Makes one’s head spin. So let’s change the subject.

Megan McArdle disagrees with “a very common” point I made in an earlier post: that banking regulation is necessary because of moral hazard that results from deposit insurance (both formal FDIC insurance and the informal insurance where authorities end up compensating creditors not covered by the FDIC program). Yes, it’s a very common point, but it turns out to be wrong, she says:

Almost everything in the world has negative and/or positive externalities. But despite this, we do not intervene to subsidize everything with good negative externalities, or punish everything with bad. That's because things with substantial negative externalities often contain sufficient punishment to deter the individual; likewise, things with positive externalities often carry enough reward to produce a socially optimal amount. For example, if I am a bus driver, the negative externality of my suddenly jerking the steering wheel to the left and driving the bus off a cliff is much higher than the cost to me--many lives against my one. But my own life is very valuable to me. The threat of its loss is enough to deter such behavior 99.9999% of the time.

The problem with this example is that in the real world the bus driver has a continuous range of options as to how much care to take. Suppose, for example, that he slept badly the night before and knows that he will not be able to drive very attentively. He may well decide to drive even though he would not if he fully internalized the risk of harm to the passengers. We have all done this, and all kinds of laws and regulations, with the tort system as an overall backstop, attempt to deter people from acting in this way. McArdle continues:

Bankers take risk in order to make money, and they control risk in order to avoid losses. But the losses they are most interested in are not to their shareholders. Rather, they are worried about the loss of their jobs. As long as the bank regulators fire any managers who put the bank in receivership, I can see no difference between an unregulated private system without deposit insurance, and a system with. That isn't to say that there is enough regulation in either situation. But if there is a problem, it is that bankers have a socially less-than-optimal risk appetite, or that the punishment for driving a bank into insolvency is insufficient. The moral hazard from deposit insurance doesn't much enter into it.

In a world with bank insurance but without regulation [corrected, thx to traveler456], I would start up a Posner bank, ask you for a deposit, and then use your money to buy lottery tickets. If I win the lottery, I pay you back; if I don’t, I dissolve the bank and you go to the government for your funds. I wouldn’t bother to hide my investment strategy from you; you wouldn’t care because you would be paid in any event. I would set up hundreds of banks and give the managers a salary that they would receive if and only if they collect deposits and use them to buy lottery tickets; otherwise, they are fired. (Corporate law junkies will point out that the government will pierce the corporate veil and go after my lottery winnings, but in the real world, with thousands of shareholders and not-lottery but still risky investment schemes that unfold over decades during which dividends are paid and the money spent, that’s not so easy.) McArdle continues:

The moral hazard for depositors may be large. But I doubt it. Most depositors are not capable of determining whether a bank is faulty or sound, and they weren't in 1830, either.

This can’t be true. In the nineteenth century, elaborate efforts were made to keep track of bank risk. Merchants discounted bank notes after consulting books that compiled risk estimates. The notes of larger and more stable banks were discounted less. Since people often made payments with bank notes, they must have had a sense of how risky different banks were, and taken the risk into account when making deposits, to say nothing of common memory about which banks have stayed in business and for how long. Today, people don’t pay attention to bank risk because of deposit insurance; but people certainly think about risk when they make uninsured investments, for example, when they buy stocks or corporate bonds or, for that matter, stereos and personal computers. She concludes:

The reason that deposit insurance requires tighter regulation is that the government wants to minimize the cost to itself--not society, for whom the losses would be the same whether the government or the bank paid them. I think this is wise, for many reasons. But not because of moral hazard.

The argument here seems to be that we should distinguish the perverse incentives of depositors and of bankers. Depositors have a perverse incentive to ignore the riskiness of a bank; ironically, the government does little to counter this incentive aside from capping the insurance payout (and not very credibly). One could imagine a different system where the government tried to regulate depositors the way insurance companies normally regulate insured parties—by demanding that the insured bear some of the risk with a copayment or deductible and take other actions to minimize the potential loss.

Instead, the government goes after the banker. This would be like an insurance company trying to regulate the activity of people who impose risks on insured parties rather than on the insured parties themselves. Imagine that I have health insurance and the insurance company tries to shut down the local polluter so as to minimize its expected insurance costs. Our system of banking regulation resembles this approach.

But moral hazard is the right term. Economists use the term moral hazard to refer to the perverse incentives that arise when a principal pays an agent to act in a certain way that benefits the principal where the agent would rather act differently, but cannot observe the agent’s action, so the agent acts in a way that ends up hurting the principal relative to a baseline of optimal behavior. There are various ways of mitigating moral hazard: one is to share risks, but another is to confine the agent’s choice set. That is what government banking regulation does. It reduces moral hazard by depriving insured depositors of the option of investing in a risky bank, which would presumably offer a high interest rate or other advantages.

The Happy Holidays/Merry Christmas Controversy:

Co-bloggers Eric Posner and Eugene Volokh have written learned, insightful posts on whether or not it is offensive to say "Merry Christmas" or "Happy Holidays" to people who aren't Christian. My own view is that the whole issue is vastly overblown. As Eugene often reminds us with respect to other issues, it's usually a good policy to avoid getting offended without a very compelling reason. There is no such thing here.

Non-Christians shouldn't take offense because some casual acquiantance wishes them "Merry Christmas." It's pretty unlikely that this is a serious attempt at conversion or an effort to put down atheism or non-Christian religions. By the same token, Christians and political conservatives shouldn't take offense if someone says "Happy Holidays." It's fairly certain that this isn't an effort to denigrate Christmas; nor is it PC hypersensitivity. Despite Bill O'Reilly's fulminations about the supposed "War Against Christmas," the position of Christmas and Christianity more generally are quite secure in American society. Just go to any shopping mall or workplace holiday Christmas party if you doubt it.

There is more than enough genuine religious prejudice in the world that we shouldn't invent bogus reasons to take offense. When it comes to this particularly pseudo-controversy, we would all be better off if everyone would just lighten up.

Happy Generic Holiday

“Happy Holidays” irritates Eugene. He says that the generic quality of the greeting gets under his skin; “Merry Christmas” is fine with him. But why should the generic quality of a greeting bother him? What could be more generic than “Hello”? But I bet that “Hello” does not bother Eugene.

I suspect that what annoys Eugene is that the person who says “Happy Holidays” to him is afraid of offending him. The person knows or suspects that Eugene is Jewish and worries that “Merry Christmas” would offend a Jew. Odd to think that you can irritate a person by trying not to offend him! But the key here is the presumption that Eugene is religious and, more to the point, thin-skinned about his religion. The person who says “Happy Holidays” to Eugene reveals that he believes that Eugene is thin-skinned and priggish and presumes that Eugene is religious when Eugene in fact is a relaxed and good-natured fellow and not religious at all (or so I assume). No wonder Eugene is annoyed.

The problem for the interlocutor who perhaps does not know Eugene well is that some people would be offended by “Merry Christmas.” That greeting also presumes a great deal—namely, that the addressee is Christian or relaxed about religion or thinks of Christmas as a secular holiday. When that presumption turns out to be wrong, offense occurs. There is no doubt that “Happy Holidays” is a lower risk greeting than “Merry Christmas. The flight to generality occurs when people know each other less well and thus know less about their religious views and overall temperament. All in all, “Happy Holidays” is less presumptuous than “Merry Christmas;” so why does it annoy Eugene?

The answer is that more generic greetings (and other practices such as gift-giving) reflect social distance (as Eugene, says a way to "play it safe"); generic greetings should really only annoy when they are conveyed by people who are close to us. If a person who celebrates Christmas receives a greeting of “Happy Holidays” from his spouse or child or friends, the greeting would seem a bit chilly, and one would suspect that something is wrong. And if you celebrate and care about Christmas, a hearty “Merry Christmas” from a stranger sounds warmer than “Happy Holidays” because, it turns out, the stranger has something more in common with you than the stranger who says “Happy Holidays.” The stranger is engaging in a high-risk, high-return strategy; a generic “Happy Holidays” is less likely to offend a non-Christian even if it sounds chilly.

Eugene might have had in mind someone who knew him well when complaining about “Happy Holidays,” perhaps a colleague or student. Otherwise, he’s being a bit hard on people. Or perhaps he is annoyed by the general tendency for people to adopt increasingly bland and, sometimes, euphemistic terms in order to avoid the risk of offense in all circumstances. The fear of giving offense—especially to ethnic and religious minorities, and people who do poorly for various reasons (uneducated, lower class, disabled, and so forth)—is ubiquitous in our society, but we should be used to it by now. Social distance is the price we pay for diversity. We avoid excluding some people by being remote to everyone.

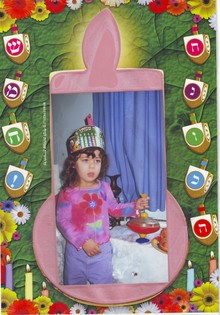

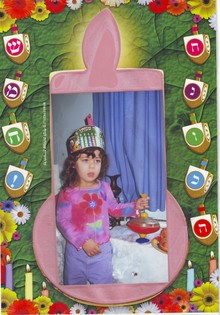

Happy Hanukkah From Israel!:

The letters on the dreidels spell "Happy Hanukkah" in Hebrew. Natalie is spinning a giant dreidel, and modeling a menorah hat. Sufganiot (Hanukkah donuts) are in the backdrop on the right.

Friday, December 26, 2008

Damage Caps and Medical Malpractice VII

My next set of posts will be on the impact of damages caps on access to medical services. Because it is hard to measure access directly, and most of the available measures lack political salience, the debate usually focuses on the number and specialty of physicians practicing in the state. This is a problematic measure for all sorts of reasons, but let's just take it as a given for now.

The focus can get extremely specific. In the debate over enacting a damages cap in Illinois (ultimately enacted in 2005, and currently under review by the Illinois Supreme Court), as this article observes, "the phrase 'there are no neurosurgeons south of Springfield' came to represent the threat of the medical liability issue. . ."

This claim was picked up and repeated by physicians, legislators, and tort reform advocates. Consider a few examples.

There's this article, titled "Illinois physicians say insurance rates are driving them out of state," and quoting a family physician (Dr. Mark Dettro):

"We are losing all these doctors to other states where they have caps on pain and suffering," Dettro said. "There will no neurosurgeons south of Springfield in Illinois. If you have a car wreck in Southern Illinois then the odds aren't very good for you."

Dr. Ed Ragsdale was quoted to the same effect in this article:

This has been an uphill battle. We’ve lost

all our neurosurgeons south of Springfield and it’s even affecting those in Chicago."

It wasn't just doctors. Legislators picked up on this talking point. U.S. Representative Mark Steven Kirk issued a press release that repeated the claim, and asserted that the problem was spreading:

South of Springfield, there are no neurosurgeons treating patients suffering from head traumas," said Kirk. "This crisis of care is now spreading to Chicago's suburbs. With only three neurosurgeons caring for patients in Lake County, we face the growing threat that our doctors will not be there when we need them most. If we do not enact reforms soon, patients will die.

Tom Cross, the Illinois House Republican leader repeated the claim in a eight page briefing package on the need for medical liability reform.

Finally, a prominent magazine for hospital trustees, repeated the claim and provided some geographic context.

According to the American Association of Neurological Surgeons, high malpractice premiums mean there are currently no neurosurgeons practicing south of Springfield, Ill.--an approximately 200-mile gap to the Missouri border.

You hear variations of such claims a lot in tort reform debates. I'm going to spend some time outlining what we found in Texas when we took a look at the access issue. But first, let me make a few preliminary points about such claims. Here’s a couple of questions worth asking, the next time you hear a claim like this:

1. Is the claim true? Are there, in fact, no neurosurgeons in Illinois south of Springfield? As far as I can tell, this appears to have been an accurate claim — but anyone who spends any time around political debates knows that the claims one hears sometimes bear little resemblance to objective reality. So, its worth asking "how do you know?" The fact that the American Hospital Association issued a undated fact sheet that says there is one neurosurgeon south of Springfield, and President Bush gave a speech on January 5, 2005, stating that there were two neurosurgeons practicing south of Springfield suggests that some additional fact checking might be in order.

2. Even if the claim is true, is it framed in a way that is nonetheless misleading? Might using state borders (no neurosurgeons in Illinois south of Springfield) to define the issue be problematic, when demand for medical services does not necessarily respect those borders? Carbondale, Illinois, where Southern Illinois University School of Law is located, is 176 miles by car from Springfield, and 107 miles by car from St. Louis. If it turns out there are plenty of neurosurgeons in St. Louis, should we care (as much, or at all) that there are no neurosurgeons in Illinois south of Springfield?

3. To what extent is the in-state demand for neurosurgical services being met by other specialists? This question is not applicable to a fair chunk of what neurosurgeons do — particularly in trauma cases — but it is worth asking about access claims regarding many other specialties, where the same or substitute services can be performed by other specialists.

4. How tight is the fit between the remedy and the problem? If we enact a damages cap, will we get more neurosurgeons south of Springfield? How many more? Will they be good neurosurgeons? Could we get too many neurosurgeons south of Springfield?

5. If we are convinced we want more neurosurgeons south of Springfield, Is a damages cap the best way to do that? Would a direct subsidy for neurosurgeons willing to locate south of Springfield be more cost-effective? If we have a fixed amount of $$ to spend on the problem, is it better spent on subsidizing relocation of neurosurgeons, or of patients needing neurosurgery (by subsidizing a system of air ambulances, for example)?

6. What are the other consequences of adopting a damages cap, apart from the effect on the supply of neurosurgeons south of Springfield? What will the effect be on other specialties, and the way in which health care is delivered? What will the effect on patients?

These are the kind of questions that it often makes sense to ask about policy initiatives — particularly ones framed by the use of salient anecdotes, such as "there are no neurosurgeons south of Springfield."

End-of-Year Open Thread:

What's on your mind?

Thursday, December 25, 2008

"Statutory Rape" in The Reader:

Ann Althouse discussed Kate Winslet's rejection of the term "statutory rape" for the relationship in The Reader (Winslet's new movie) between a woman in her mid-30s and a 15-year-old boy. As best I can tell, Ann does take the view that the behavior is indeed properly labeled "statutory rape," both legally and morally. [UPDATE: Ann's update reveals that I misunderstood her; I now think her view is that the behavior may well be treated as "statutory rape" from a moral perspective, but she doesn't take a stand on the legal issue. Still, the interviewer whom she quotes seems to suggest that the behavior might be condemned on the grounds that it's a crime, so the legal issue seems to still be worth discussing.]

1. As to the legal question, in the country where the movie is apparently set — Germany — sex between an adult and a 15-year-old is now generally not statutory rape: The age of consent there is 14. I don't know what it was in Germany in the late 1940s, but I can say that in many American states it was 14 until the 1990s (the latest to change, I believe, was Hawaii, around 2000). Throughout much of American history, the age of consent was 15 or less (often significantly less).

As I note in this post, even if you focus solely on the Western World (the U.S., Europe West of the Iron Curtain but including all of Germany and excluding the pinpoint countries, plus the Western Anglosphere, which is to say Australia, Canada, and New Zealand), 38% of the population lives in countries with the age of consent set at 15 or less. If you include South Korea and Japan in the West, the percentage will climb even higher.

Now none of this tells us what the age of consent should be, or how seriously the law should take sexual relationships between adults and people slightly under the age of consent. But it does suggest that we can't just conclusively assume that a fictional relationship in a movie, set in a different time and place, can be treated as "statutory rape" simply because today all American states would treat it as such, though today many Western countries would not treat it as such, and until recently some American states wouldn't treat it as such.

2. I can't speak in detail to the moral question, since I haven't seen the movie, and I don't know the social context of the time. While some crimes, such as forcible rape, are in my view wrong regardless of the social or personal context, other matters — statutory rape, copyright infringement, underage drinking, and the like — tend to turn on much subtler factors, and the arbitrary lines that the law necessarily draws can't precisely track the underlying moral truth.

I will say that my intuition is that 15-year-old boys are unlikely to suffer lasting emotional harm from affairs with 30-something-year-old women, any more than from any first sexual relationship, whether at 15 or 16, and whether with a 35-year-old or another 15-year-old. (I wouldn't claim this extends to 15-year-old girls with older men, but I don't think one should blithely disregard factors such as the sex of the parties in making the moral judgment here.) Of course, maybe that's just my remembered teenage fantasies (not, I should stress, my personal experience) talking. Perhaps I'm mistaken on it. But again I'm hesitant to say that such relationships can categorically be seen as deeply immoral behavior regardless of person, time, and place.

3. The parenthetical in the Althouse post, "By the way, the actor playing the role was only 17 when most of the scenes were filmed. They did some last minute filming of the naked parts 'literally days' after he turned 18," raises separate questions. I would assume that this was all done legally, and as a moral matter, I doubt that the actor is going to suffer any real harm from the experience; I expect he's going to derive a great deal of professional and likely personal benefit from it. But again I can't claim any expertise on that.

Note: In the factual discussion above, I refer to the age of consent for sex between a typical adult and a minor. I don't include — since The Reader doesn't deal with this — sex between people close together in age, where the age of consent is often set lower. I also don't include situations where there's some familial or authority relationship between the parties, where the age of consent is often higher.

UPDATE: Ann Althouse responds in an update to her original post; I'm busy with family stuff today, but I hope to have a chance to read it and perhaps reply in turn tomorrow.

Want To Wish Me a Merry Christmas?

Be my guest! (Not that you owe it to me, just like you don't owe Orin a beer.)

I don't celebrate Christmas as a religious holiday, but so what? If you wish me a Merry Christmas, is it really reasonable for me to interpret this as a wish that I have a deep relationship with Jesus on this day? I rather doubt it -- "Merry [anything]" isn't much of a call for serious religious action or introspection. Nor is it an assumption that I'm religiously Christian. Everyone, certainly including religious Christians, knows that tens of millions of Americans, including those raised nominally Christian, don't celebrate it as a religious holiday.

Perhaps saying "Merry Christmas" is a reflection of the fact that most of America is culturally Christian, in the sense that it celebrates traditionally religious holidays. But that is indeed a fact. Saying "Happy Holidays" won't hide it, and saying "Merry Christmas" hardly rubs it in anyone's face (especially given the Santas and other paraphernalia you're in any event likely to see all around).

Moreover, Christmas is a day off for people without regard to religion (except for those who work in businesses that require them to work that day, there probably also largely without regard to religion, except for the comparatively devout). Chances are that your Jewish colleagues are doing something fun for Christmas. I am, and I had done that each year even before I married my culturally Christian wife. Why shouldn't we be merry on these occasions?

So if you tell me "Merry Christmas," good for you. If you tell me "Happy Holidays," I confess I'll get a bit annoyed because of its generic air, but I'll just assume that you're trying to play it safe -- often a very good strategy in social relations. Plus why be churlish about someone wishing you a happy anything? If you tell me "Happy Hanukkah," I'll start racking my brains about when Hanukkah actually is this year; I never have any idea. If you tell me "Happy Diwali," I'll assume that this is a good thing in your life, and I'll appreciate the good wishes. (If neither you nor I are Hindu, then I might wonder what you mean by that.) If you tell me "Happy New Year," my favorite greeting, I'll be extra pleased, but that's just a matter of taste.

So, Merry Christmas, everyone -- yeah, all you Russian Orthodox, too, I know all about your old calendar, but you're in a Gregorian country now, buddy. And best wishes for a happy new year!

Wednesday, December 24, 2008

What is the “ownership society”?

This term cropped up on in a recent NYT article which blames the financial crisis on Bush administration policies, including its advocacy of an ownership society. The article goes too far: the financial crisis is the result of bipartisan regulatory decisions going back decades and the Fed’s easy money policies—and it is important to understand that financial crises will almost certainly occur even when government regulators do everything right. They are like hurricanes: we can blame the government for failing to build strong levees but not for failing to stop the hurricane from forming over the Atlantic ocean. If the hurricane is bad enough, even strong levees will do no good. (A lot of people also blame market actors but that does not make much sense. People act rationally or greedily or stupidly, as they always have, and blaming them for the financial crisis is just another way of arguing that government regulation was inadequate. Might as well blame hurricanes for destroying cities.)

But what is the “ownership society,” anyway? It is a political slogan that the Bush administration apparently first used in 2003 to refer to three of its policy goals: (1) privatization of Social Security; (2) the creation of private health care accounts; and (3) subsidization of home ownership. The underlying theme is that it is better if people own than if they do not own, but what does this mean? Ownership compared to what?

The Social Security example suggests one interpretation: ownership compared to government sponsorship. In one scenario, people earn wages, a portion of their paycheck goes to the government, and then, much later, they receive money back from the government. They don’t own anything, though they might have a reasonable expectation that the government will eventually pay something that bears some relationship to the payroll tax. In the ownership scenario, the sum of money that would otherwise be used for Social Security can be invested in securities. Note an odd feature, from a market or libertarian perspective: people don’t have true ownership rights in their labor; they are obligated to put a portion of the return on their labor into an account. Their “ownership” of securities in that account therefore does not reflect a commitment to a free market in some pure sense. What is true is that risk and return is increased, which is a normal feature of ownership. If you invest unwisely, or wisely but unluckily, you will end up impoverished when it comes time to retire. As a result, people have strong incentives to think about retirement, and to inform themselves about financial instruments and the likely future of the economy. Whatever you might think of this outcome—some people find it appealing, others do not—the odd thing is that if you like the idea of people having control over their finances rather than being dependent on the government, then you should want to do away with Social Security altogether rather than privatize it. Let people decide how much to spend and how much to save, as well as how they save their money. The ownership society in this setting boils down to the claim that we should subsidize investment and penalize consumption. If that is really the goal, why not just advocate a consumption tax and do without the ownership metaphor?

Let’s turn to home ownership. Here, the compared to what question seems to be—compared to renting an apartment or perhaps renting a government-subsidized apartment or living in public housing. If government subsidizes home mortgages, then people who would otherwise rent or live in public housing are more likely to buy their own home. Again, the effect of channeling people into ownership is to increase the risk and the payoff. If you rent an apartment, and its value appreciates, you don’t obtain the return—your landlord does. If its value declines, you aren’t hurt—your landlord is. Finance theory tells us that investments have higher payoffs when they are riskier, and this is true for owning a home just as it is true for owning a piece of stock in a business. It was also thought, as in the case of Social Security privatization, that people who own homes will end up being better citizens: they will invest more in their homes, which will improve the neighborhood and hence the home values of others; they will care more about the future and therefore they will inform themselves about politics and vote responsibly; they will join the rentier class and become Republicans.

The problem with this theory, as I noted yesterday, is that ownership does not have any intrinsic value. It is often wise to rent rather than own, as everyone understands from everyday life, and we might think that low-income people who chose to rent apartments rather than buy them knew what they were doing. Home ownership has some attractive features—you needn’t fight with your landlord, or worry that he will terminate the lease—but it is basically an enormous financial gamble that many people, particularly low-income people, shouldn’t make. Your neighborhood, for reasons outside of control, could become worse over the years; in addition, you might find that you need to move for family or employment reasons. If you are a low-income person, most of your savings will be tied up in your home, which means that you will be inadequately diversified against these future risks. These basic truths were obscured for many years because home prices tended to increase and not to collapse during recessions, but home ownership is just a kind of investment and does not enjoy immunity from the business cycle.

Home ownership policy of the Bush and Clinton administrations was, in essence, an attempt to pay low-income people to make a risky investment that they would otherwise rationally avoid. I cannot understand why anyone would think that such a policy would be sensible. In some cases, these people will do well and enjoy the upside of their investment, but in other cases they will do poorly, with the result that they will be worse off than ever.

Reboot the FCC:

Larry Lessig has an interesting column in Newsweek today calling for the dismantling of the FCC:

The solution here is not tinkering. You can't fix DNA. You have to bury it. President Obama should get Congress to shut down the FCC and similar vestigial regulators, which put stability and special interests above the public good. In their place, Congress should create something we could call the Innovation Environment Protection Agency (iEPA), charged with a simple founding mission: "minimal intervention to maximize innovation." The iEPA's core purpose would be to protect innovation from its two historical enemies—excessive government favors, and excessive private monopoly power.

Lessig has always been a hard guy to pin down politically (a compliment). Though he is sometimes caricatured as something of a doctrinaire liberal, his views are usually much more nuanced and interesting than that label suggests, and this is a good example. While people on "the right" have been calling for abolition of the FCC for years, it's interesting (and possibly important, given that Lessig probably has, if not Obama's ear directly, certainly the ear of those who have Obama's ear ...) that those more closely aligned on "the left" are making the argument now. I think he's on to something -- minimal intervention to maximize innovation and to curb monopoly power (whether government-created or not) sounds like good policy to me (though the devil, here as elsewhere, is probably in the details).

"Twenty Years On: Internalising the Fatwa":

A very interesting column in the Spiked Review of Books by Kenan Malik, author of the forthcoming From Fatwa to Jihad: The Rushdie Affair and its Legacy. An excerpt:

For many, the controversy seemed to come out of the blue. For many, too, especially in the West, the image of the burning book and the fatwa seemed to be portents of a new kind of conflict and a new kind of world. From the Notting Hill riots of the 1950s to the Grunwick dispute in 1977 to the inner-city disturbances of the 1980s, blacks and Asians had often been involved in bitter conflicts with British authorities. But these were also, in the main, political conflicts, or issues of law and order. Confrontations over unionisation or discrimination or police harassment were of a kind that was familiar even prior to mass immigration.

The Rushdie Affair seemed different. It was the first major cultural conflict, a conflict quite unlike anything that Britain had previously experienced. Muslim fury seemed to be driven not by questions of harassment or discrimination or poverty, but by a sense of hurt that Salman Rushdie’s words had offended their deepest beliefs.

Twenty years later, the Rushdie Affair seems equally like a conflict from a different age -– but for the opposite reason. Not only have the issues that it raised -– the nature of Islam, and its relationship to the West; the meaning of multiculturalism; the boundaries of tolerance in a liberal society; the limits of free speech in a plural world –- become some of the defining problems of the age. But the politics of the pre-Rushdie age are now what seems anomalous.

It has now become widely accepted that we live in a multicultural world, and that in such a world it is important not to cause offence to other peoples and cultures. As the sociologist Tariq Modood has put it: ‘If people are to occupy the same political space without conflict, they mutually have to limit the extent to which they subject each others’ fundamental beliefs to criticism.’

Obama’s Report Does Not Mention the Two Corrupt Contacts Alleged To Have been Ordered by Blagojevich.

The Report released Tuesday by the Barack Obama camp discloses, not only direct contacts between the Obama staff and Governor Blagojevich and his staff, but two other specific indirect contacts. It does not, however, disclose the only two contacts mentioned in the U.S. Attorney’s complaint and affidavit by which Blagojevich directed intermediaries to convey his corrupt bargain to the Obama camp.

Perhaps they occurred; perhaps they didn't. Obama's Report never says.

Valerie Jarrett. Here is the US Attorney’s affidavit regarding a Nov. 12 conversation in which Blagojevich asked a SEIU union official (almost certainly Tom Balanoff) to convey his interest in a job to Valerie Jarrett (or another Obama staffer):

109. On November 12, 2008, ROD BLAGOJEVICH spoke with SEIU Official, who was in Washington, D.C. Prior intercepted phone conversations indicate that approximately a week before this call, ROD BLAGOJEVICH met with SEIU Official to discuss the vacant Senate seat, and ROD BLAGOJEVICH understood that SEIU Official was an emissary to discuss Senate Candidate 1’s interest in the Senate seat.

During the conversation with SEIU Official on November 12, 2008, ROD BLAGOJEVICH informed SEIU Official that he had heard the President-elect wanted persons other than Senate Candidate 1 to be considered for the Senate seat.

SEIU Official stated that he would find out if Senate Candidate 1 wanted SEIU Official to keep pushing her for Senator with ROD BLAGOJEVICH. ROD BLAGOJEVICH said that “one thing I’d be interested in” is a 501(c)(4) organization.

ROD BLAGOJEVICH explained the 501(c)(4) idea to SEIU Official and said that the 501(c)(4) could help “our new Senator [Senate Candidate 1].” SEIU Official agreed to “put that flag up and see where it goes.”

110. On November 12, 2008, ROD BLAGOJEVICH talked with Advisor B. ROD BLAGOJEVICH told Advisor B that he told SEIU Official, “I said go back to [Senate Candidate 1], and, and say hey, look, if you still want to be a Senator don’t rule this out and then broach the idea of this 501(c)(4) with her.”

Did Balanoff convey this message? The Obama Report never says one way or the other.

The Obama camp does disclose what is probably the earlier conversation referred to in the affidavit:

On November 7, 2008 — at a time when she was still a potential candidate for the Senate seat — Ms. Jarrett spoke with Mr. Tom Balanoff, the head of the Illinois chapter of the Service Employees International Union (SEIU). Mr. Balanoff is not a member of the Governor’s staff and did not purport to speak for the Governor on that occasion. But because the subject of the Governor’s interest in a cabinet appointment came up in that conversation, I am including a description of that meeting. Mr. Balanoff told Ms. Jarrett that he had spoken to the Governor about the possibility of selecting Valerie Jarrett to replace the President-Elect. He told her that Lisa Madigan’s name also came up. Ms. Jarrett recalls that Mr. Balanoff also told her that the Governor had raised with him the question of whether the Governor might be considered as a possible candidate to head up the Department of Health and Human Services in the new administration. Mr. Balanoff told Ms. Jarrett that he told the Governor that it would never happen. Jarrett concurred.

Mr. Balanoff did not suggest that the Governor, in talking about HHS, was linking a position for himself in the Obama cabinet to the selection of the President-Elect’s successor in the Senate, and Ms. Jarrett did not understand the conversation to suggest that the Governor wanted the cabinet seat as a quid pro quo for selecting any specific candidate to be the President-Elect’s replacement. At no time did Balanoff say anything to her about offering Blagojevich a union position.

[That Jarrett did not see a quid pro quo in Blagojevich's desires was previously stated in the Report:

Nor did she understand at any time prior to his arrest that the Governor was looking to receive some form of payment or personal benefit for the appointment.]

There are several details to note about these two paragraphs in the Report:

As noted, this is a different conversation than the one that Blagojevich on Nov. 12 requested the SEIU official to make. Steven Greenhouse of the New York Times quotes a source at SEIU as saying, “All the official did, they said, was listen to Mr. Blagojevich and his chief of staff and ferry some messages for them.” Note that Jarrett claims that, though a job for Blagojevich was broached, she did not consider it a quid pro quo. There is no statement one way or the other whether Jarrett informed Obama or anyone else in the Obama camp about the job(s) Blagojevich wanted. Jarrett's denial is much narrower than Emanuel's and does not cover the 501c(4). Her denial is: “At no time did Balanoff say anything to her about offering Blagojevich a union position.” It does not mention “the idea of this 501(c)(4)” that Blagojevich requested on Nov. 12 to be conveyed to her. Further, this denial is much narrower than an earlier denial in the Report regarding Emanuel’s contacts: “There was no discussion of a cabinet position, of 501c(4), of a private sector position or of any other personal benefit to the Governor.” Regarding the Nov. 7 conversation, the statement “Mr. Balanoff . . . did not purport to speak for the Governor on that occasion” does not foreclose the possibility that Balanoff did purport to speak for the Governor on a later date. The NY Times’s union source said that he did “ferry some messages” for the Governor.

Individual A. The other indirect contact mentioned in the affidavit is this one:

Nov. 13: “ROD BLAGOJEVICH asked Advisor A to call Individual A and have Individual A pitch the idea of the 501(c)(4) to “[President-elect Advisor].” Advisor A said that, “while it’s not said this is a play to put in play other things.” ROD BLAGOJEVICH responded, “correct.””

There is nothing in the Report about this contact, if it occurred.

Dr. Eric Whitaker. The second indirect contact disclosed in the Obama Report, one previously unknown, is between Dr. Eric Whitaker and a Deputy Illinois Governor:

In the period immediately following the election on November 4, 2008 – on either November 6, 7 or 8 – Deputy Governor Louanner Peters called him at his office and left a message. When he returned the call, Ms. Peters asked who spoke for the President-Elect with respect to the Senate appointment. She explained that the Governor’s office had heard from others with recommendations about the vacant seat. She stated that the Governor’s office wanted to know who, if anyone, had the authority to speak for the President-Elect. Dr. Whitaker said he would find out.

The President-Elect told Dr. Whitaker that no one was authorized to speak for him on the matter. The President-Elect said that he had no interest in dictating the result of the selection process, and he would not do so, either directly or indirectly through staff or others. Dr. Whitaker relayed that information to Deputy Governor Peters.

Dr. Whitaker had no other contacts with anyone from the Governor’s office.

Observations:

Note that, unlike the Jarrett disclosure above, the Whitaker disclosure ends with a blanket denial of further contacts: “Dr. Whitaker had no other contacts with anyone from the Governor’s office.” Note that no dates are given for when Whitaker relayed the information that “The President-Elect said that he had no interest in dictating the result of the selection process.” It wouldn’t surprise me if this message was not sent to Peters until the campaign started putting out the word on Nov. 10 that Jarrett was no longer a candidate for Senate.

Rahm Emanuel. In the section on Rahm Emanuel’s discussions with Blagojevich and his staff is this interesting statement:

In those early conversations (Nov. 6-8) with the Governor, Mr. Emanuel recommended Valarie Jarrett because he knew she was interested in the seat. He did so before learning — in further conversations with the President-Elect — that the President-Elect had ruled out communicating a preference for any one candidate. As noted above, the President-Elect believed it appropriate to provide the names of multiple candidates to be considered, along with others, who were qualified to hold the seat and able to retain it in a future election.

The Report implies that Emanuel’s 5-6 early discussions with Blagojevich and his staff about the Illinois Senate seat were not authorized by Obama. That would be surprising, but not impossible. If we ever see the transcripts of these conversations, it will be interesting to see whether Emanuel purported to be acting for himself or for Obama.

Bottom line: The Report discloses that Valerie Jarrett was informed of Blagojevich’s interest in a cabinet position, but is silent on whether she was informed of his desire for a lucrative job with a charity. Further, the Report is silent about whether Obama himself knew of Blagojevich’s interest in a cabinet or charitable job.

Obama’s Report does not purport to be a complete list of all the contacts between his staff and emissaries for Blagojevich, only of direct contacts between the two staffs, plus two specifically disclosed indirect contacts. The Report does not indicate one way or the other whether the two contacts mentioned in the government’s affidavit by which Blagojevich intended to have his desire for a lucrative job conveyed to the Obama camp ever took place. It mentions the contacts made by people who had not (at the time of the conversations) been directed to shake down Obama, but fails to mention the two contacts (if they occurred) by people who had (according to the Government’s affidavit) been recently directed to contact Obama staffers to discuss simultaneously the Senate seat and Blagojevich’s desire for a job.

Assuming that Obama is not operating under any restrictions from Patrick Fitzgerald, when Obama returns to work in a week or so, it will be up to the press to find out from him whether the two corrupt contacts alleged in the affidavit to have been ordered by Blagojevich ever occurred and whether Obama learned before December that Blagojevich was seeking a job.

Do Subjective Expectations of Privacy Matter in Fourth Amendment Law?:

The Supreme Court has said that government conduct is a Fourth Amendment "search" when two conditions are met: 1) the person searched had a subjective expectation of privacy, and 2) that expectation of privacy was objectively reasonable. When I teach Fourth Amendment law, I explain to students that, in my view, the two tests are really one: the "reasonable" expectation of privacy is the only thing that actually matters.

I think that's true for a few different reasons. First, the government has the burden of proof of showing that a defendant lacked a subjective expectation of privacy. As a practical matter, the government can rarely satisfy that burden: It is quite uncommon for the government to know exactly what a defendant was thinking at the time of the search. Second, most people don't expect that the police are about to break in. Third, in the few cases when the government can prove that the defendant lacked a subjective expectation of privacy, the defendant will normally lack an "objective" expectation of privacy anyway. As a result, the subjective prong won't do any work. Finally, the Supreme Court in Smith v. Maryland suggested (albeit inartfully) that in the strange circumstances where a defendant lacked a subjective expectation of privacy but would have had a reasonable expectation of privacy, the usual two-step test would be suspended and replaced with a solely "normative inquiry" (that is, an objective test). See Smith v. Maryland, U.S. 735, 740 n.5 (1979). For all these reasons, I have tended to think that the two-step test is really just one step: The subjective prong doesn't really matter.

That's been my impression, at least, and that's what I teach to my students. But my impression raises an empirical question: Are there any cases, federal or state, in which a court held that no "search" occurred because a defendant lacked a subjective expectation of privacy, even though such an expectation would have been objectively reasonable if it had existed?

I don't know of any such cases, at least off the top of my head. Do any readers know of any examples of this? If you do, please leave a comment. Thanks!

Tuesday, December 23, 2008

A President's Lawful Authority to Respond to a Nuclear Attack:

In a recent interview with Chris Wallace, Vice President Cheney made the following claim about a President's ability to launch a counterstrike if the U.S. came under nuclear attack: The president of the United States now for 50 years is followed at all times, 24 hours a day, by a military aide carrying a football that contains the nuclear codes that he would use and be authorized to use in the event of a nuclear attack on the United States. He could launch a kind of devastating attack the world's never seen. He doesn't have to check with anybody. He doesn't have to call the Congress. He doesn't have to check with the courts. He has that authority because of the nature of the world we live in. Over at Slate, Dahlia Litwick calls this claim a blunt demonstration of "the Nutty Version of the Unitary Executive Theory," and describes it as Cheney's "biggest whopper of the week": The claim that "the nature of the world we live in" warrants a perennially unchecked executive branch can be delivered with all the gravitas in the world, and it still amounts to constitutional nonsense. Notwithstanding the difference between an unchecked executive and a unitary one — that is, the difference between executive powers that cannot be controlled by the other branches and an executive branch in which whatever executive power exists is ultimately controllable by the President — isn't Cheney correct that, under the usual understanding of Article II, a President has this power in the event of a nuclear attack?

I'm not an expert in the caselaw here, but I had thought that this was settled in The Prize Cases, 67 U.S. 235 (1862): If a war be made by invasion of a foreign nation, the President is not only authorized but bound to resist force by force. He does not initiate the war, but is bound to accept the challenge without waiting for any special legislative authority. And whether the hostile party be a foreign invader, or States organized in rebellion, it is none the less a war, although the declaration of it be 'unilateral.' . . .

Whether the President in fulfilling his duties, as Commander-in-Chief, in suppressing an insurrection, has met with such armed hostile resistance, and a civil war of such alarming proportions as will compel him to accord to them the character of belligerents, is a question to be decided by him, and this Court must be governed by the decisions and acts of the political department of the Government to which this power was entrusted. "He must determine what degree of force the crisis demands." To be clear, I am not making a normative argument about what the law should be. In addition, I am not defending the Vice President's view of Article II more broadly. Rather, I'm just wondering if it's Vice President Cheney, rather than Dahlia Litwick, who has better described the mainstream understanding on this particular legal question.

UPDATE: Several readers believe I have misread Lithwick's column: They suggest that Lithwick was not singling out the point Cheney made in the paragraph she excerpted, but rather was meaning to criticize the broader perspective of Article II that Cheney was making elsewhere in the interview. I don't quite see that, but I am happy to flag the possibility that the misunderstanding was mine: Needless to say, if Lithwick agrees with the Cheney quote she excerpted, then it seems there is no real disagreement here.

Does the Financial Crisis Discredit Libertarianism:

In my view, what we are seeing today is the unwinding of multiple bubbles, starting with the stock market bubble in the late 90s, the housing bubble of the mid-2000s, and the most recent mini-bubble in commodities. These bubbles all have a common source, which was lax monetary policy coming out of central banks. These lax policies were meant to cushion the impact of multiple crises, starting with the crisis in 1998 that arose from the Russian default and the plunge in Asian markets through 9/11. Banking authorities, most notably Alan Greenspan, thought they had inflation under control because consumer price inflation was under control (thanks, largely, to the huge boon to consumers of globalization; consider all the unbelievably cheap "made in China" products on the shelves), and came up with all sorts of rationalizations as to why ASSET price inflation was not really inflation. The incompetence of the relevant authorities in understanding asset price inflation is demonstrated by the fact that Greenspan bought into the idea that housing prices wouldn't fall nationwide because they never had before--forgetting that the underlying increase in housing prices was itself unprecedented. Greenspan obviously believed, against all relevant historical data, that the run up in prices was a natural result of market forces.

In short, we can argue from here to eternity over exactly what pro-free market or pro-regulatory U.S. government policies precipitated the crisis as it specifically developed. But if I'm right that the underlying problem was overly lax monetary policy, which sent false signals to the market regarding the true price/value of money and the amount of real wealth that was being created, it seems to me that even if financial sector/housing policy had been infinitely wise, the bubble would have developed in another sector where policy was less wise, and would have also caused serious economic dislocation when it popped.

Keep in mind also that putting aside all of the debate about what the Bush Administration, Congress, Clinton, et al., did or did not do, the housing bubble was not an American phenomenon, but was as bad or worse in various parts of Western Europe, Eastern Europe, and Asia, which, I'm guessing, have about as broad a range of regulatory policies regarding both housing and finance as one can reasonably expect. The prior stock market bubble was also a worldwide phenomenon, as was, of course, the commodities mini-bubble. This again suggests that the problem was a worldwide misapprehension by central bankers of the consequences of their actions, and not some specific pro or anti free market policies pursued by the U.S. government (not to say that wiser policies couldn't have helped mitigate the damage at some point, especially by cracking down on leverage when there was still time, one of the apparently forgotten lessons of the Great Depression...)

As Eric Posner suggests below, the pure libertarian solution--a free market in money, with no central bank intervention--is not even on the table among "serious thinkers."

And I'm not even going to argue that the pure libertarian solution is the right one. But if the blame is accurately placed primarily on central bank policy, then it's rather foolish to consider this a failure of libertarianism or free markets.

It is, on the other hand, an example of the failure of a particular libertarian, Alan Greenspan. Somehow, perhaps for ideological/psychological reasons, he appears to have seen himself as a champion of an anti-regulatory ideology, even though he was the most powerful regulator in the world, and was artificially reducing the cost of money. It would be hard for even the best satirist to come up with a figure like Greenspan, an objectivist who wielded more government power over the economy than any other individual in the world, used that power incompetently, and then allowed himself to believe (at least twice) that bubbles that his policies helped create were the result of the "free market" and needed to be left alone.

UPDATE: One more thought. Libertarians of the utilitarian school often oppose government regulation not because they think that all government regulation is inherently illegitimate, or even necessarily bad, but because on balance they think that decisions made through the political process, or by regulators (like Greenspan) acting with limited information, are likely in most cases to be less sound than decisions made through decentralized market processes. It seems to me that many of the bad decisions made, both on the pro (Fannie, Freddie, Community Reinvestment Act, etc.) and anti (failure to regulate derivatives, leverage, etc.) were not the result of any particular ideology, but the natural result of the political process. One problem with the inevitable "mixed economy" that we live in, and which libertarians would predict, is that the political process will often give us the worst possible result--privatization of profit, socialization of risk. Related Posts (on one page): - Does the Financial Crisis Discredit Libertarianism:

- Does the financial crisis discredit libertarianism?

Does the financial crisis discredit libertarianism?

Ilya says no; others say yes. The question is not a good one, however, because libertarianism, in any meaningful philosophical sense, hasn’t influenced financial policy in decades. One might as well ask whether the financial crisis has discredited Jeffersonian republicanism or nineteenth century rural populism.

The real question is whether the financial crisis has discredited the pro-market, deregulatory movement in a general sense, or banking deregulation in particular. Neither Weisberg nor Huffington know enough to answer this question, which is extremely complicated, and will be the subject of debate for decades. A few preliminary thoughts here:

1. Americans reject unregulated banking, as have people in every country around the world. A truly “libertarian” or free market system would lack deposit insurance and a central bank—a system that existed in the United States in the nineteenth century. Such a system is certainly possible—it did exist—and it may even be optimal in some long-term-we’ll-all-be-dead sense. But it creates extraordinary volatility that people greatly dislike. If you lend to (that is, deposit with) an unregulated bank, you might get a good interest rate, but you have no remedy if the bank becomes insolvent. This gives rise to bank runs, financial contagion, and panic. Most people simply don’t want to take the chance that the place where they park their money will vanish and take their funds with it; hence the popularity of the government guarantee. In addition, because banks borrow from each other, the collapse of one can lead to the collapse of others, drying out credit, and harming the real economy. A government backstop is and has been political bedrock for decades. The government acts as lender of last resort through a central bank, depository insurance, and the rest. No serious person rejects this system in any modern economy.

2. If you have government-supplied insurance, then you have to have government regulation of people’s financial activities. There is no way to avoid this conclusion. In a world without such regulation, banks would make excessively risk loans because they get the upside and the taxpayer bears the cost of the downside. Banks would also keep insufficient capital on hand to pay off depositors. And depositors, unlike ordinary creditors, would have no reason to investigate banks and ensure that they are operated safely. Although many people have criticized Depression era banking regulation—especially the constraints on the geographic reach of banks and the division between regular and investment banking—no serious person denies that if the government insures banks, then it must regulate them. The least controversial type of regulation is the minimum capital adequacy requirement, which obliges banks to keep a certain amount of cash or other liquid assets on hand to meet spikes in withdrawals. Unfortunately, there is nothing simple about these rules: in principle, the amount of capital kept on hand should be a function of the riskiness of the bank’s portfolio. In practice, this is hard to do. But the basic principle is undisputed.

3. Over the years, there has emerged an academic and political debate about the optimal amount of banking regulation. Again, no serious—or, at least, influential—person taking part in this debate has disputed the need for some kind of insurance or lender-of-last-resort function. And no serious person has disputed the need for restrictions on what banks and other financial institutions that benefit from insurance can and cannot do. The debate was about a matter of degree. One camp believed that existing regulation was excessive; another camp believed that existing regulation was either adequate or insufficient. The two sides converged on many issues: for example, geographical restrictions did not reduce the riskiness of banking but in fact made it harder for banks to spread risks. So both sides could agree on this type of “deregulation.”

4. The current financial crisis suggests, to the extent that one can draw inferences from one observation, that deregulation did go too far. Regulators and (probably) market actors appear to have overestimated the extent to which people could protect themselves from risk by purchasing various types of credit insurance on the market and in other ways diversifying their assets. Regulators may, alternatively or in addition, underestimated the extent to which government insurance caused people to engage in risky behavior by taking advantage of financial innovations that allowed them to evade minimum capital requirements and other regulations—on banks, insurance companies, and investment banks. If you are more heavily regulated if you own 30 years loans and less regulated if you own equivalent mortgage-backed securities, then you will sell the former and buy the latter, and take on more risk. There is certainly reason to think that some tweaking, perhaps serious tweaking, is in order. But it is tweaking nonetheless.

5. As Ilya notes, the Bush administration did contribute to the crisis, but not by promoting free market ideology or “libertarianism.” Instead, it foolishly advocated what it called an “ownership society,” one in which people would be encouraged to own homes (and health care accounts and retirement funds), through, as it turned out, artificially cheap credit, subsidies, and the like. There is no reason in the world to think it is better, in some abstract sense, to own your home than to rent it—any more than it is better to own DVDs than to rent them from Netflix. For some people, ownership is better; for others, renting is better. There was tremendous intellectual confusion here: there is a difference between helping the poor (for example, by giving them money) and rearranging the legal relationship between them and the goods and services they use (for example, paying them to own rather than rent). The main effect of this policy was to subject lower-income people to more risk—of the upside, to be sure, but also of the downside. When the housing bubble pops, and the economy tumbles into recession, any serious commitment to the idea of ownership requires that our new owners suffer their losses. But the Bush administration could not sustain the harsh implications of its philosophy, especially because it was complicit in encouraging people to take on risk who might otherwise have been more cautious.

The Bush administration pursued a two-track policy, then, one that both cut back on financial regulation and channeled financial activity toward the housing sector. The latter most definitely contributed to the financial crisis, though it is unclear how much. The former may well have but this question is even more difficult. Deregulation may have been hasty or ill-considered; that is not the same thing as saying that it could have been done better, and that therefore the lesson of the financial crisis is not that deregulation is bad but that the particular deregulatory approach of the Bush administration (and Congress, and the Clinton administration, etc.) was poorly thought out—a point that could be made about the deregulation of the S&L industry in the 1980s, which was also poorly thought out and disastrous as a result, and yet the more-or-less elimination of that sector was sensible. Deregulation may also have gone too far, which is not the same as saying that some degree of deregulation was sensible—a position that is held by most economists.

6. The moral of this story is that we live in a society with a highly regulated financial sector. It will remain highly regulated in the future, and the difficult problem now is to determine what the optimal type and level of regulation is. This is mostly a technocratic question that rests atop a rough social consensus that the government should trade off risk/volatility and growth. True libertarianism has made no headway against this consensus; it remains as irrelevant today as it has been since the 1930s. Related Posts (on one page): - Does the Financial Crisis Discredit Libertarianism:

- Does the financial crisis discredit libertarianism?

Seeking Little-Discussed Gun Control Laws:

We often hear, or have heard, about various gun control laws — bans on concealed carry, restrictive carry licensing schemes, bans on gun possession by felons or violent misdemeanants, bans on gun possession by people who are the targets of restraining orders, waiting periods for purchases, and so on. But I'm looking for gun control laws that are less talked about, the sorts of laws that even people who follow gun debates in some measure might say "Huh, I'd never thought of that one."

Naturally, the judgment about which laws are little-discussed is likely to be impressionistic, but let me offer three examples. First, some states entirely ban gun possession by noncitizens; I haven't heard that discussed often, though some such state laws have been struck down by courts. Second, some states ban handgun possession — though not long gun possession — by 18-to-20-year-olds, and Illinois seems to seriously limit even long gun possession by 18-to-20-year-olds, though a note from your parent (if he isn't himself a felon, a nonresident alien, and so on) might get you out of that constraint.

Third, some states, including my own California, neither entirely ban open carrying in most public places nor entirely allow it (as other states are well known to do), but rather allow it only if the gun is unloaded. That means you can carry a gun visibly strapped to your hip and a magazine visibly strapped to the other hip, and load the gun for immediate self-defense if you have a couple of seconds, but you can't have the magazine in the gun. (This is how I read the statute, especially Cal. Penal Code § 12031(g), but I'm not a specialist; don't actually act on my casual reading if your liberty depends on it!) To be sure, you might attract untoward attention by such open carrying, but the law technically allows it, so long as no rounds are actually in the weapon.

So these are some examples; do you have more? Again, please avoid the gun control laws that are often talked about in the media — I know about them already, and so do most of our readers. Also, more details are always better; if you have a citation or a URL to such a statute, that would be great, and if you just have a hazy recollection, it would be very helpful if you could clear it up a bit.

Finally, city and county ordinances, as well as administrative regulations, are especially likely to be missed by researchers, including by me. If you have some pointers to surprising local or administrative gun controls, I'd especially love to see them.

UPDATE: I originally said that in California you could carry an unconcealed unloaded gun, and a magazine in your pocket, but Gene Hoffman kindly pointed out that People v. Hale, 43 Cal. App. 3d 353 (1974), suggests that a gun may be treated as concealed if its magazine is concealed. I'm not sure that's a proper interpretation of the statute, but it does still seem to be a binding precedent, so that's what California law appears to be. Many thanks to Gene for the correction.

Does the Financial Crisis Discredit Libertarianism? Round II:

Arianna Huffington has a widely circulated op ed claiming that the current economic crisis discredits free markets. She provides very little in the way of evidence. There isn't much here that wasn't aired in Jacob Weisberg's similar piece back in October. So I refer interested readers to my rebuttal to Weisberg in this post. Huffington even imitates Weisberg's comparison between free market advocates and communists. This, I suppose, is the economic policy debate equivalent of comparing the Israelis to the Nazis and is about equally edifying.

Huffington also cites the recent New York Times article claiming that the crisis was caused in part by the Bush Administration's supposed commitment to free markets. I'm not going to analyze the article in detail here. However, I will note that it also emphasizes that the Bush administration engaged in considerable government intervention incentivizing financial institutions to issue mortgages to poorly qualified homebuyers as part of its policy of promoting homeownership. As the article puts it:

Mr. Bush had to, in his words, “use the mighty muscle of the federal government” to meet his goal. He proposed affordable housing tax incentives. He insisted that Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac meet ambitious new goals for low-income lending.

"Us[ing] the mighty muscle of the federal government" doesn't exactly sound like laissez-faire to me.

More generally, the notion that the Bush Administration had any serious commitment to free markets is laughable in light of the fact that it created the largest new government program in decades (the 2003 Medicare prescription drug bill), presided over the greatest expansion of government spending since the 1960s, and massively increased regulatory spending as well.

Happy Saturnalia!

Today is the last day of Saturnalia, the ancient Roman winter festival. Congratulations to our many Roman pagan readers!

Here's what Saturnalia involved, according to the Encyclopedia Romana:

During the holiday, restrictions were relaxed and the social order inverted. Gambling was allowed in public. Slaves were permitted to use dice and did not have to work. . . Within the family, a Lord of Misrule was chosen. Slaves were treated as equals, allowed to wear their masters' clothing, and be waited on at meal time in remembrance of an earlier golden age thought to have been ushered in by the god. In the Saturnalia, Lucian relates that "During My week the serious is barred; no business allowed. Drinking, noise and games and dice, appointing of kings and feasting of slaves, singing naked, clapping of frenzied hands, an occasional ducking of corked faces in icy water—such are the functions over which I preside."

Although Saturnalia is ending, it's not too late to take advantage of the inversion of the social order. Professors switching places with students fits well with the Roman custom of slaves switching places with masters. So if any of my students want to grade the huge pile of Property exams currently awaiting my ministrations, you are more than welcome!

Motion for New Trial After Sequestered Jurors Allegedly Had Sex:

From the St. Louis Post-Dispatch: Eight years ago, a juror in a capital murder trial notified the judge that two other jurors had sex while sequestered — and that two sheriff's deputies guarding them had sex too.

Now the man convicted of second-degree murder in that case is demanding a new trial on a claim that his lawyers did not do enough to persuade the judge that the escapades tainted the verdict.

The issue is back before St. Louis Circuit Judge Julian Bush, who presided over the 2000 trial of Roberto Dunn, now 34, who was convicted of killing his girlfriend's mother.

In August 2000, about two weeks after the conviction, Bush got a letter from a juror making the accusations. "Sexual liberties by deputy sheriffs were rampant also," the letter read.

. . .

In her letter, [the juror] accused two jurors of having sex with each other during two evenings at a hotel where the panel stayed. She said jurors believed the two sheriff's deputies assigned to the case were having sex with each other while on duty at the hotel.

"Acts of sex and insubordination were scandalous and unspeakable …" Thompson wrote. She testified in the recent hearing that she heard sexual noises coming from the next hotel room. As long as the jurors weren't discussing the case with each other, I would think this is okay.

Bush v. Gore, and The Meaning of Cases:

Adam Liptak has an interesting piece in this morning's New York Times about the precedential significance of Bush v Gore (issued 8 years ago this month). The opinion itself contained unusual (and arguably unique, for a Supreme Court opinion) limiting language: “Our consideration is limited to the present circumstances,” the majority famously said, “for the problem of equal protection in election processes generally presents many complexities.” But as Liptak points out, a number of recent cases have apparently disregarded this limitation and relied on the decision for a more general principles applicable to a broader range of circumstances than those presented in the original case.

For you law students out there, it's a very important object lesson. Like any legal opinion, Bush v. Gore can "mean" many different things; there are inevitably many different ways to characterize its "holding," and you can't tell which one is "correct" just by reading the opinion, however carefully and skillfully you do so. Ultimately, its meaning will determined by what happens subsequent to the decision itself, in the ways in which later courts use it and apply it in future cases. In one view, Bush v. Gore holds, in Liptak's words, that "a court-supervised statewide recount violates equal protection guarantees when it treats similar ballots differently by instructing local officials to use new and insufficiently specified standards." Or, it might have held that "once a state grants the right to vote on equal terms, it may not by later arbitrary and disparate treatment, value one person’s vote over that of another” -- a much broader meaning for the decision, and one that will be applicable to many more cases. [The latter reading is the one given to the case by the Sixth Circuit in its recent ruling allowing the challenge to Ohio's election law to proceed].

Fourth Amendment Rights in Numbers Dialed Stored Inside a Cell Phone:

I recently came across an interesting Fourth Amendment case in which a district court judge ruled that a defendant has no privacy rights in the list of phone numbers stored inside his cell phone: United States v. Fierros-Alavarez, 547 F. Supp.2d 1206 (D. Kan. 2008). This conclusion is wrong, I think, and why it's wrong raises an interesting aspect of Fourth Amendment law.

The facts of the case are simple. The defendant was arrested and taken into custody, and a cell phone was taken from him at the time. The next day, the officers began to suspect that the cell phone stored records of criminal activity. Specifically, the officers believed that the defendant was a participant in a narcotics conspiracy, and that there would be records of calls to other members of the conspiracy inside the phone. Acting without a warrant, an officer searched three parts of the phone: He looked at its “phone book” directory that stores names and telephone numbers, and he recorded the five names found there. He checked the recent calls directory that retains the telephone numbers of missed, received or dialed calls, and he wrote down the telephone numbers for the twenty recent calls. He checked the picture and video file but found nothing. The evidence was later used against the defendant to prove the case against him, and he moved to suppress the evidence on the ground that the officer violated his Fourth Amendment rights in looking through the phone. To resolve that issue, the court first addressed the threshold issue of whether the officer's retrieving the phone numbers violated the defendant's reasonable expectation of privacy.

That threshold question forced the court to choose between two different lines of cases. On one hand, there are the cases concluding that a defendant normally has a reasonable expectation of privacy in the contents of data stored in his phones, pagers, and computers. On the other hand, there is Smith v. Maryland, 442 U.S. 735 (1979), in which the Supreme Court held that it does not violate a defendant's reasonable expectation of privacy to install a "pen register," a device for recording the numbers dialed from a particular phone line, at the office of the phone company.

The basic question for the district court in Fierros-Alavarez was whether the Fourth Amendment rule for retrieving numbers dialed for a phone should follow the precedent for the device or the precedent for the data. The court concluded that the case was governed by Smith, and that therefore retrieving the data was not a search: The government argues the holding in Smith and the later applications of Smith logically extend to the issue presented by the facts of this case so as to preclude an expectation of privacy in the recent call directory as well as the phonebook directory. The defendant's only rejoinder is that a phone book directory may disclose more information than that revealed in a pen register. The defendant, however, has not shown that the phone book directory in his cellular telephone discloses more than the “addressing information”-the telephone number and the subscriber's name-on the same numbers appearing in the recent calls directory. On the record as it stands, the court must conclude that the defendant has not carried his burden of proving a reasonable expectation of privacy in the addressing information retrieved from the recent calls directory and in the names and numbers taken from the phonebook directory. Thus, the court denies the defendant's motion for lack of standing. Wrong conclusion, I think. The general rule for Fourth Amendment searches is that privacy rights are determined ex ante by the place in which the search occurs, not ex post by whether the evidence turns out to be private. If a person has a storage device like a phone, computer, or package, Fourth Amendment rights are determined by whether the person has rights in the storage device, not whether the particular information discovered was sufficiently "private" to deserve Fourth Amendment protection.

The leading case here is probably Arizona v. Hicks, 480 U.S. 321 (1987). In Hicks, an officer entered an apartment under exigent circumstances to try to find and stop a person who was firing gunshots from inside the apartment. Once inside, the officer saw very expensive stereo equipment in what was otherwise a squalid apartment. Suspecting that the equipment was stolen, the officer picked up the equipment to see the serial numbers so he could run the numbers for hits with known stolen property. In an opinion by Justice Scalia, the Court held that moving the equipment to reveal the serial numbers was a search: It matters not that the search uncovered nothing of any great personal value to respondent - serial numbers rather than (what might conceivably have been hidden behind or under the equipment) letters or photographs. A search is a search, even if it happens to disclose nothing but the bottom of a turntable. That rule makes a lot of sense, I think. The police shouldn't be allowed to go through your private stuff so long as they only look for and take information that is in some sense "non-private." If you write a diary entry and describe going for a walk in the park, the police shouldn't be allowed to break into your home, rifle through your stuff, read your diary, and then take the entry about walking in the park all on the theory that the fact that your walk in the park was "public."