|

Saturday, April 7, 2007

Banning Laptops in Class:

Georgetown law professor David Cole explains why he banned laptops from this class:

Some years back, our law school, like many around the country, wired its classrooms with Internet hookups. It's the way of the future, I was told. Now we are a wireless campus, and incoming students are required to have laptops. So my first-year students were a bit surprised when I announced at the first class this year that laptops were banned from my classroom.

I did this for two reasons, I explained. Note-taking on a laptop encourages verbatim transcription. The note-taker tends to go into stenographic mode and no longer processes information in a way that is conducive to the give and take of classroom discussion. Because taking notes the old-fashioned way, by hand, is so much slower, one actually has to listen, think and prioritize the most important themes.

In addition, laptops create temptation to surf the Web, check e-mail, shop for shoes or instant-message friends. That's not only distracting to the student who is checking Red Sox statistics but for all those who see him, and many others, doing something besides being involved in class. Together, the stenographic mode and Web surfing make for a much less engaged classroom, and that affects all students (not to mention me).

I don't think it is a big surprise that Professor Cole is pleased with the results. Perhaps more interesting is the fact that many of his students were too.

How does banning laptops work in practice? My own sense has been that my class is much more engaged than recent past classes. I'm biased, I know. So I conducted an anonymous survey of my students after about six weeks — by computer, of course.

The results were striking. About 80 percent reported that they are more engaged in class discussion when they are laptop-free. Seventy percent said that, on balance, they liked the no-laptop policy. And perhaps most surprising, 95 percent admitted that they use their laptops in class for "purposes other than taking notes, such as surfing the Web, checking e-mail, instant messaging and the like." Ninety-eight percent reported seeing fellow students do the same.

After wireless was installed in all of our classrooms, we adopted a classroom computer use policy at Case limiting laptop use to class-related activities. I share David's concern about laptop use, particularly the natural tendency to let transcription replace actual note-taking and the potential for one student's non-academic use to distract his or her classmates. I mention the policy at the start of every semester, but I generally trust my students not to abuse their laptop privileges, knowing full well that some students are surfing the web, or worse (particularly in the back). Nonetheless, I have been reluctant to ban laptops from my classes. Given Cole's experience, I might need to reconsider. [For my reconsideration, see the comments.]

[LvHB]

UPDATE: Rick Garnett has thoughts at PrawfsBlawg here.

Google Directions:

Go to Google Directions, and enter in the boxes Boston and London. Thanks to Haym Hirsh for the pointer.

Ohio AG Sues Paint Makers for "Public Nuisance":

On Monday, new Ohio attorney general Marc Dann filed suit against several paint manufacturers alleging that they contributed to a "public nuisance" by manufacturing lead paint decades ago. (See also here.) Lead paint remains in many older homes where it can pose a risk to children if not properly contained or remediated. RightAngleBlog has collected some responses to the suit here.

Rotten Tomato Raid by Pullman Police:

This is a good reason not to use grow lamps to grow tomatoes in your closet. [LvIP]

[Note to local officials: That water pipe in my office was a just prop for a recent law school event on the "Bong Hits 4 Jesus" case. Honest.]

"The Vindication of Major Mori":

David Luban has an interesting post at Balkinization on the plea bargain of David Hicks and the controversial defense strategy of Major Michael Mori.

This outcome seems like poetic justice, because the result spectacularly vindicates Maj. Mori’s decision to go to Australia to try to arouse political indignation about Hicks’s imprisonment – and Colonel Davis had threatened to press charges against Mori for violating a military-law prohibition on speaking disrespectfully of high U.S. government officials. Mori didn’t back down, and we now see that his tactical decision to focus on political sentiment in Australia was exactly the right one for his client.

For more commentary from various perspectives on the Hicks plea bargain and sentence, see the AIDP blog.

Did Speaker Pelosi Commit a Felony?

Setting aside whether House Speaker Nancy Pelosi's amateur effort at shuttle diplomacy was wise or effective, did she violate the Logan Act and commit a felony during her visit to Syria? Robert Turner thinks the answer could be "yes." Ms. Pelosi's trip was not authorized, and Syria is one of the world's leading sponsors of international terrorism. It has almost certainly been involved in numerous attacks that have claimed the lives of American military personnel from Beirut to Baghdad.

The U.S. is in the midst of two wars authorized by Congress. For Ms. Pelosi to flout the Constitution in these circumstances is not only shortsighted; it may well be a felony, as the Logan Act has been part of our criminal law for more than two centuries. Michael Dorf thinks otherwise. Among other things, Dorf notes that "no one has ever been convicted of violating the Logan Act, and no indictments have even issued in the last 200 years." Even if one thinks Speaker Pelosi violated the letter of the law, Dorf notes, "There is zero chance that Pelosi will actually be prosecuted." Moreover, there are many arguments she could make in her defense.

That Pelosi's conduct was legal, does not mean it was appropriate or politically astute. Here's more Dorf on Pelosi from Dorf on Law: The Constitution is best read to forbid congressional freelancing (to be distinguished from such things as congressional factfinding missions to foreign countries for the purpose of oversight of appropriations and related matters). Speaker Pelosi may undermine her public position on Iraq---where the Constitution clearly contemplates a substantial role for Congress---by asserting authority in an area where the Constitution truly supports Presidential prerogative.

UPDATE: More from Michael Dorf and Marty Lederman here.

Let me also make a plea for greater civility in the comments. I believe this is an interesting issue that can be discussed without partisan vitriol or name-calling.

SECOND UPDATE: Perhaps Pelosi should take diplomacy lessons from Bill Richardson.

Friday, April 6, 2007

As Professor Shmoe Says:

Here's a tentative conjecture I have about effective legal writing: Legal writing tends to be better if you give scholars you quote credit in footnotes, not in the text. Thus, for instance,

Professor X has insightfully expressed the argument that the disruption inquiry subjects speech to a "heckler’s veto"; that is, the "content- or viewpoint-based listener reactions" of co-workers, superiors, or the public are a determining factor of the scope of employee speech protection.

is generally better written just as

The disruption inquiry subjects speech to a "heckler’s veto"; that is, the "content- or viewpoint-based listener reactions" of co-workers, superiors, or the public are a determining factor of the scope of employee speech protection.

(I assume of course the quote from X is attributed in a footnote, and I don't want to discuss how else, if at all, this sentence can be improved.)

Why do I say this?

1. The reader wants to see what you're arguing. Who said it first generally doesn't matter. What matters is the argument that's being made; and while "Professor X has insightfully expressed the argument that" is not a vast digression or distraction, it is something of one.

2. The reader also wants to know what you are arguing. Whether deliberately or not, "Professor X has insightfully expressed the argument that" is unclear on whether you fully endorse the statement. It looks like you are, but it's not completely clear. "As Professor X has argued," is less ambiguous, and seems to commit the author more clearly to what comes after; but even that's not as clear as just saying what you're asserting, and giving the credit in the footnotes.

3. Especially when a lot of people are credited, the article begins to look more like a literature survey, a summary of what others are saying. You want the article to come across as what you are saying. Of course, give credit where credit is due, but footnotes take care of your obligations just fine.

Now there are some exceptions to this general suggestion. Professor X's statement may be important precisely because he says it, for instance if he's a very big gun (e.g., what Nimmer of Nimmer on Copyright says is important because he's Nimmer), if he's a judge whose opinions are therefore especially likely to be influential, if he has special knowledge of the underlying facts (e.g., if he's writing about his own experiences dealing with some case), or if his view may seem surprising for him (e.g., "even Professor Laurence Tribe has endorsed the individual rights of the Second Amendment"). The statement may also be so closely associated with some concept or viewpoint that mentioning the professor may help remind people about the concept. And there are doubtless some other situations in which naming the scholar in the text is a good idea: In some fields or subfields, the "Professor X says .... And Professor Y argues ...." style is so common that it might be expected by at least some readers, though my sense is that general legal scholarship (or for that matter briefs addressed to courts) is not such a field.

But in general, my sense is that mentioning professors' names is needlessly distracting. The motive may well be laudable -- graciously give credit to those who have influenced your thinking -- but the result is less effective than if you stick with the substance, and give credit in the footnotes.

I likewise wouldn't encourage people to name authors of arguments that you want to rebut, for instance,

Professor X has argued that the disruption inquiry subjects speech to a "heckler’s veto"; but this is mistaken because [argument].

Here, the alternative is something like (with all the appropriate footnotes that cite X)

Nor does the disruption inquiry subject speech to a "heckler's veto." [Argument.]

or, better yet, something that frames the argument affirmatively but that rebuts the "heckler's veto" argument in the process. Here too the alternative is somewhat briefer and less distracting; but, as importantly, it depersonalizes the disagreement as much as possible. Especially if your argument is very effective, there's no reason to make it look like an attack on Professor X (something that X or his friends may be unusually sensitive to). Focus on what you're saying, and on why the contrary views are mistaken, and not on who holds the contrary views.

Now again there are exceptions to this rule. Sometimes, for instance, if X is well-known, you may want to make clear that you're taking him on, because that shows that you have the guts and ambition to take on the top people. But this rarely works, and in any event, even if that's reason to take on some of the big guns by name, the rule should still remain: Leave the text for the substance, and put people's names in the footnotes.

I should stress that this is a conjecture about what is most effective. It is not a theory about what's "wrong," or even a conjecture that the approach I counsel against is highly ineffective.

At the same time, I hope it's more than just an esthetic preference of mine. I'd love to hear your views on it (at least in part because I'm contemplating adding it to the third edition of my Academic Legal Writing book, and I'd like to vet it with my blog readers first).

"Gun Used in Self-Defense?"

The ABC News site asks:

Have you ever defended yourself from a crime in your home, in your business, or in public by using a gun? Perhaps you warded off a potential attacker by simply showing a gun?

40 states now allow their citizens to obtain conceal-carry permits for handguns. Some people say that's dangerous, while others say it allows them to protect themselves.

If you have a story of self-defense involving the aid of a gun and would like to tell it to 20/20, please fill out the form below. A "20/20" producer may contact you.

To fill out the form (if you do have such a story), go here. I hasten to add that I can't speak to the likely quality of the resulting story -- the story may use representative incidents or unrepresentative ones, may describe them thoughtfully or sensationally, and so on. Still, I thought it was worth noting the inquiry.

Thanks to Paul Hsieh for the pointer.

Hooking Your Computer Up To Government Owned Networks and Fourth Amendment Protection:

This week, the Ninth and Tenth Circuits have each decided interesting cases on how the Fourth Amendment applies when a person hooks up their personal computer to a government-owned computer network, leading to a search of the personal computer by a government official. I'd like to blog about both opinions at length, because there is a lot here -- some of it right, some of it a bit off. But in the meantime I'll just note the opinions: United States v. Heckencamp (college student connects to college network; retains REP in his computer, but remote search by university system administrator okay under "special needs" exception) (hat tip: Tom Cross); United States v. Barrows (town government employee who brought computer to work and connected it to townn's internal network on permanent basis lost reasonable expectation of privacy in machine's contents). Very interesting cases.

ABC News Site on the Yale Flag-Burning:

From an online survey at the ABC News site: Three Yale students have been arrested on charges of arson, reckless endangerment and other crimes for allegedly burning a flag on the porch of their apartment. One of the students translated for U.S. troops in Afghanistan. None have criminal records.

Should flag burning be a crime?

Yes. The flag is one of our most important symbols and desecrating it should be illegal.

No. What the students did is unfortunate, but they are protected by the First Amendment.

I'm not sure. I need more information. The only trouble: They have apparently been arrested not for burning a flag on their own porch, but for burning a flag belonging to someone else, while it was still attached to his home; on top of that, the "flames [had] reached the building's awning." So, yes, that sort of flag burning should be a crime -- the crime of arson and reckless endangerment. And ABC News should be a little more careful in its reports.

Thanks to Greg Pollowitz (National Review Online's Media Blog) for catching this, and to InstaPundit for the pointer.

United States v. Askew and the Scope of Investigative Stops:

The D.C. Circuit handed down an interesting stop-and-frisk case involving an officer's unzipping a suspect's jacket during an investigative stop, revealing a gun. Judge Kavanaugh (joined by Judge Sentelle) ruled that the unzipping of the jacket was a permissible part of the investigative stop; Judge Edwards dissented on the ground that the unzipping of the jacket exceeded the scope of Terry v. Ohio. The case is United States v. Askew, found via How Appealing. A quick summary of the facts: The defendant was identified in the street as a possible suspect in an armed robbery nearby, and was brought before an eyewitness of the robbery to see if the eyewitness recognized him. Before the ID procedure, the officer had conducted a "pat down" that hadn't revealed any weapons. Next, the officer partially unzipped the suspect's jacket to help an eyewitness identify whether the suspect was in fact the robber. When unzipping the jacket, the officer felt a hard object that blocked him from being able to unzip the jacket all the way. However, he did not stop to investigate further at that time. Finally, after the identification procedure was over, the officer unzipped the jacket the rest of the way, revealing a black pouch with part of a gun sticking out. It later turned out that the suspect was not the armed robber; he just happened to have been walking near the scene of the robbery with a gun in a black pouch on his person. The suspect was charged with gun offenses, and argued that the unzipping of his jacket violated his Fourth Amendment rights. I think this is a very close case, and after thinking about it for a while I'm not sure where I come out. My initial instincts were that Edwards was right, because Terry allows an investigative stop and a protective search for weapons but not an investigative search. Judge Kavanaugh makes two arguments in support of the view that Terry does allow investigative searches, but neither seem terribly strong. First, he argues that fingerprinting can be allowed during Terry stops, and that these are intrusions much like unzipping a jacket. However, unzipping a person's jacket is plainly a search of his person; fingerprinting generally is thought not to be a search (although some lower courts disagree). Second, he notes that Fourth Amendment scholar Wayne LaFave has suggested that he thinks some limited investigative searches during Terry stops should be okay. But with all due respect to my co-author Wayne LaFave, his personal opinion about what the law should be is not the same as what the law is. On the other hand, this case does seem different from the usual case, in that the first partial unzipping was not really investigatory. Its purpose was to expose what the suspect was wearing underneath his jacket so the eyewitness could help identify whether the suspect was the robber, not to find something underneath the jacket. Given that, it seems plausible that you should subject the initial unzipping to a general Terry reasonableness analysis, as Judge Kavanaugh does. As for the reasonableness analysis, it seems plausible too, although it's hard to know without knowing more details. Was removing the jacket really helpful to the ID process, given that the jacket underneath was apparently already visible (as suggested by the fact the officer ended up not bothering to remove the jacket after the zipper became stuck when it hit the hard object)? On the other side, is unzipping a person's jacket really just a de minimis intrusion on his privacy, as Kavanaugh suggests? (slip op at 13). Perhaps, but I'm not entirely sure. I also have some doubts about the second unzipping. Was the second unzipping really about officer safety? If the officers were really concerned about their safety, why wait until the show-up was over to continue to unzip the jacket? Anyway, very interesting case.

Privatization and the Law and Economics of Political Advocacy, Part 4 -- Miscellaneous Points on the Model:

This post continues my series on my upcoming Stanford Law Review paper on Privatization and the Law and Economics of Political Advocacy (see here for the technical paper). The last post set out the basic economic model -- read that post, if you haven't already and if you want to understand this post. This post just elaborates a bit on the basic model -- and applies it to prisons -- before we go on to apply the model to the real world and prisons.

* * *

If one accepts the fundamental assumption of this Part—that the probability of success only depends on the total amount of money in the pot—this simple model is flexible enough to accommodate many institutional details of privatization. The total free-riding result happens whenever one sector has a lower threshold than the other, for whatever reason. In this story, you and your competitor are identical except that you have 90% of the industry and he has 10%. But one’s threshold could be lower for other reasons as well.

For instance, suppose that, to add insult to injury, the government not only breaks you up but also subjects your revenues to a high (50%) tax rate. The breakup already altered your spending threshold by making all your curves shift down to 90% of their previous level (see the figures in the previous post). Now, with the 50% tax, your revenue and marginal revenue curves shift further down—to 45% of their original levels. (If your 10% competitor is subject to the same tax, his curves are 5% of the original industry curves.)

So the combination of the breakup and the tax makes you act like a 45% firm. These new percentages—call them “real” shares—no longer need to add up to 100% (in fact, with the 50% tax, they add up to 50%), but they convey the economic intuition that your spending threshold is lower when, for whatever reason, your benefits decrease.

After we determine everyone’s “real” shares, the same analysis applies as before: The “biggest” firm does all the advocacy, and the “smaller” firm free rides. The only difference is that we learn who is “biggest” not just by looking at proportions of the market but at shares of total industry revenue. Instead of calling this firm “biggest,” we’ll call it the “dominant” firm. Thus, if the tax rate on your revenues is 90%, you will act as though your share is 9%; and if your 10% competitor is exempt from the tax, then he, with his 10% share, is actually the dominant actor. Now you will free-ride off him.

In short, anything that affects your revenues affects your “real” share. Suppose, for instance, that your competitor is less profitable than you are: Your 90% share is a monopoly share in a 90% geographic area, while the remaining 10% is divided among 100 competitors who act according to the textbook perfect competition model, where everyone makes zero economic profits. Then those competitors—and thus that entire 10% sector—act as though they had a 0% share.

Or, as a final example, suppose that your competitor is better at advocacy. Perhaps, for whatever reason (maybe he is a slicker lobbyist), each dollar of his is twice as persuasive as a dollar of yours. Then, he acts as though his share is 20%, and his threshold goes up accordingly. All these considerations affect your “real” shares for purposes of choosing how much to spend on advocacy. (In this example, he still won’t do anything because 20% is still less than your 90% share.)

This model applies straightforwardly to privatization, which splits up an industry between public and private much as the Antitrust Division could split up a monopolistic firm. To be sure, the public sector is not a “profit maximizer” like a private firm. But the concept of profit maximization needn’t be interpreted in a narrow financial sense. Government agencies—or, more precisely, people who work at the agencies and who have some control over what the agencies do—pursue goals of some sort. Whether it is the Pentagon or a state Department of Corrections, a government agency does obtain some benefit from its service provision.

Moreover, agencies are not the only actors; the employees of the agencies, through their unions, also enjoy some benefit from public provision of the service, and they can also participate in political advocacy. The challenge is to determine who the relevant actors are and what benefits they might plausibly seek to maximize. This is what I will try to do in later posts for corrections agencies and corrections officers’ unions.

The model implies, at a minimum, that some amount of privatization will decrease advocacy, for two reasons. The first reason is that, as long as the level of privatization does not exceed a certain critical threshold, the public sector will dominate (in terms of “real” share) the whole private sector combined, so the model predicts that whole private sector’s advocacy would be zero. The second reason is that as privatization increases, the benefits of service provision to the public sector fall; because the public sector is smaller than it would be without privatization, its advocacy falls.

How far can we continue to privatize before advocacy stops falling? As privatization increases, the second step always holds—by definition, privatization shrinks the size of the public sector. The first step, however, does not always hold for large enough levels of privatization. Obviously, at a certain point, the private sector can come to dominate the public sector. Then the private sector will do all the advocacy, with the public sector free-riding, and from then on privatization might increase advocacy. The level of privatization at which advocacy stops falling is a threshold that we may call an “advocacy-minimizing privatization level.”

For instance—going back to the graphical model above—suppose our two firms benefit identically from having a given proportion of the industry. Then the advocacy-minimizing breakup is a 50–50 split (or 33–33–33 if the breakup is into three firms, and so on)—because under such a split, the dominant firm is as small as it can possibly get.

If a split creates a splinter firm that is twice as profitable as the incumbent firm, or perhaps twice as slick, then the advocacy-minimizing split is 67–33, again equalizing the firms’ stake in the system. The splinter firm is half as large but twice as profitable, so again the dominant firm (in terms of “real” share) is as small as it can possibly get. Conversely, if the splinter firm is only half as profitable as the incumbent firm, the advocacy-minimizing split is 33–67.

This concept becomes useful in later posts. I will argue that for prisons, the public-sector share of total benefit is much larger than the private-sector share—first, because the public sector still has a larger industry share, and second, because private firms are subject to a more competitive regime, so their profits are fairly low. Thus, the advocacy-minimizing level of privatization is probably quite high. Within this model, it would take a lot more privatization before pro-incarceration advocacy stops falling.

This basic result—that, by fragmenting an industry, one can reduce that industry’s political advocacy to increase its market—is also consistent with empirical studies on the relationship between industry concentration and lobbying.

In general, industry concentration can have two opposing effects on lobbying. The first effect is the one discussed above: A concentrated industry can more easily overcome its collective action problems, so we should expect it to lobby more. But not all lobbying is industry-expanding; some lobbying is simply anti-competitive, seeking to regulate the market (for instance, through entry restrictions) to allow existing firms to charge above-market prices. Firms in a more concentrated industry can more easily cooperate to suppress competition in the product market, so they have less need for anti-competitive lobbying: They can raise prices above market levels all by themselves by directly using anti-competitive methods.

Thus, studies that don’t disentangle these effects can come up with results in either direction. One study found a positive effect of concentration on industry contributions, while another found that the percentage of firms in an industry that had political action committees rises and then falls as concentration goes up.

Here, though, I focus only on advocacy for reforms that increase the size of the industry, and not on advocacy for reforms that would squelch competition in the industry—since it is primarily the first sort of advocacy that privatization critics urge is illegitimate. So only the first of these forces comes into play here.

Thursday, April 5, 2007

Blankenhorn (round 2):

Last week I responded to an article by David Blankenhorn in the Weekly Standard arguing that support for SSM and non-traditional views of marriage “go together” and are “mutually reinforcing.” He based this conclusion on international survey data that shows, he claims, a correlation between recognition for SSM in a country and non-traditionalist beliefs. He also quoted from a few pro-SSM marriage radicals in academia who literally embody the tendency of these views to “go together”: they support SSM because they think it will undermine traditional marriage. I responded that, for a number of reasons, this was not a winning argument.

Now Blankenhorn has defended his argument against my criticisms. (1) First, he denies that he has “eschewed” the argument of Stanley Kurtz, based on claimed correlative data, that gay marriage has contributed to the decline of marriage in Europe. Instead, he says that he “embraces” Kurtz’s argument, and is trying only to “build” on it. (This has come as a relief to Kurtz, who initially suggested there might be some disagreement between them.) (2) Second, he argues that it is unfair of me to require him to “scientifically demonstrate” that gay marriage is contributing to non-traditional beliefs about marriage when the correlative data allow us “to make reasonable (if qualified, and modest) inferences about a likely causal relationship” between the two. (3) Third, he claims that while there may be a few anti-SSM marriage radicals who believe gay marriage will actually strengthen marriage, “the dominant, most influential idea about gay marriage” on the left is represented by the marriage radicals he cites and not those I cite. (4) Finally, he challenges me to cite a “prominent supporter” of SSM who has publicly committed to otherwise traditionalist beliefs about marriage (e.g., we should make divorce harder, discourage out-of-wedlock births, stigmatize adultery).

Let’s take these responses one at a time.

(1) The whole point of Kurtz’s work has been to show, mainly through the use of correlations, that gay marriage has caused marital decline in Europe. (Even Kurtz’s correlations are faulty, incomplete, and unpersuasive – but that’s another matter.) In his book, Blankenhorn said flatly, “These correlations [between SSM and non-traditional attitudes] do not prove that gay marriage causes marriage to get weaker. I am not trying to prove causation.” (p. 232) (emphasis original) In his Weekly Standard article, he suggests “giving up the search for causation” and looking for “recurring patterns” in the data instead.

It seemed to me that Blankenhorn was trying to distance himself, at least rhetorically, from Kurtz. I thought it was a wise decision.

(2) It is now clear that Blankenhorn’s argument is structurally and conceptually the same as Kurtz’s, only weaker. Here’s why.

There are a couple of ways one might argue that gay marriage is hurting marriage. First, one might argue that gay marriage has caused problems to marriage itself, like rising cohabitation and unwed childbirths. That is what I’d call a strong and direct claim about the harm of gay marriage. Second, one might argue that gay marriage has caused people to have beliefs about marriage that might, in turn, cause concrete harms to marriage itself. This is an indirect and weaker claim about the harm of gay marriage. Kurtz presents the former, stronger and more direct, form of the argument. Blankenhorn, it turns out, is presenting the latter, weaker and more indirect, form of the argument. Blankenhorn’s argument is thus a poor cousin of Kurtz’s.

Except for that, the arguments are basically the same. Like Kurtz, Blankenhorn relies on what he claims is a correlation to “infer” a “likely causal relationship.” (Blankenhorn is, to his credit, rhetorically more modest than Kurtz about the strength of his own argument.)

What do we make of Blankenhorn’s use of correlations? I don’t think correlations are useless. They might indicate something important is going on. By itself, a correlation could be a starting point for further investigation. It’s a clue that two seemingly unrelated phenomena may be related. But it might also seriously mislead us unless we’re very careful.

Consider the case of smoking as a cause of cancer, which Blankenhorn uses to show that correlations can be valuable because they can help show causation. Yes, there’s a correlation between smoking and cancer. But we know smoking causes cancer not simply because of this simple correlation. Instead, we know smoking causes cancer because decades of careful, replicated, peer-reviewed, and methodologically sound medical research has revealed (1) a correlation (2) that sequentially matches the harm (e.g., lung cancer often follows smoking), (3) we’ve controlled for confounding variables and (4) ruled out multiple other plausible causes of the harm (e.g., auto exhaust or coal-fired plants), (5) and we’ve identified the agent or mechanism (over 70 chemicals in tobacco) that (6) causes a harmful result (tobacco carcinogens damage DNA inside lung cells).

When it comes to gay marriage “causing” harm by leading to non-traditional attitudes about marriage, Blankenhorn gives us only the first of these six. He has only correlation. And even this, it turns out, is suspect.

I’m not just playing with words here and I’m not requiring “scientific proof” analogous to demonstrating pathological processes in the body. I’m asking for a standard degree of reliability in inferences and an accounting when the correlations seem explicable by numerous other factors and are sequentially all wrong (more on that below). There’s good reason to be suspicious of an argument that a correlation allows us to infer a causal relationship. There’s a correlation between people who buy ashtrays and people who get lung cancer, but this hardly proves that buying ashtrays causes lung cancer. If we relied on correlation, we’d think all sorts of crazy things were causally related.

Consider what can be done with a correlation used to “infer” a “likely causal relation.” People in countries without same-sex marriage are more likely to believe women should stay at home and not work, that men should be masters of their households, that there should be no separation of church and state, that people should not use contraception when they have sex, that divorce should never be permitted, and that sodomy should be criminalized. If these correlations exist, have I demonstrated the existence of a “cluster of beliefs” that reinforce one another and “go together,” undermining the arguments against SSM?

Or consider the more sympathetic correlations to SSM that Blankenhorn ignores. Countries with SSM are richer, healthier, more democratic, more educated, more liberal, have more egalitarian attitudes about women, etc. Have I shown that the absence of SSM is likely causing harm in those unfortunate backward countries that refuse to recognize it?

Here’s another correlation helpful to the conservative case for SSM: countries with SSM are enjoying higher marriage rates since they recognized it. Have I shown that SSM likely caused this?

Even Blankenhorn’s correlation is suspect, in a way very similar to Kurtz’s. Non-traditional attitudes about marriage in countries with SSM preceded the recognition of SSM, just as signals of marital decline in Europe preceded SSM. Though I haven’t gone back and checked the previous international surveys from the 1980s and 1990s, I’ll bet my mulberry tree they show that. Besides, even the survey data Blankenhorn relies on show that he’s got a problem. In one survey, the data comes from 1999-2001, before any country had full SSM. In the other survey, the data comes from 2002, when only one country (the Netherlands) had full SSM.

How could SSM have caused a decline in traditional marital attitudes before it even existed? Of course, Blankenhorn is still free to argue that non-traditional attitudes greased the way for SSM, but this doesn’t show that SSM caused or even reinforced non-traditional attitudes. What Blankenhorn needs, even as a starting point, is some evidence that non-traditionalist views rose after SSM. He doesn’t have that.

Of course, even if he had the sequence right, he’d still have the problem of trying to deal with the existence of multiple other factors that have plausibly fueled non-traditionalist attitudes. Here, too, Blankenhorn has the same problem as Kurtz. Just as we can plausibly surmise that factors like increased income, longer life spans, more education, and women’s equality – rather than SSM – have caused actual marital decline, so we can plausibly surmise that factors like these have caused a rise in non-traditionalist attitudes about marriage. And even if the data showed a rise in non-traditional attitudes after SSM, that might well only be a continuation of pre-existing trends. Kurtz has that problem, too, when he tries to show marital decline.

(3) I demonstrated in my last post that there are quite a few marriage radicals who are uncomfortable with gay marriage (either oppose it or very reluctantly support it) because they think it will strengthen marriage. That was just the tip of an iceberg, believe me. Blankenhorn says that he is familiar with these authors and cites them in his book.

But wait a second. While he mentions Michael Warner, for example, it is not to present Warner’s concern that gay marriage will reinstitutionalize marriage but as evidence of the bad reasons gay couples seek marriage (see p. 142). And while he quotes from Tom Stoddard (pro-SSM marriage radical) in the noteworthy early debate Stoddard had with Paula Ettelbrick (anti-SSM marriage radical), he omits even mentioning Ettelbrick’s influential concerns about SSM expressed in the same debate he quotes from (p. 162). (I quoted from her essay in my last post, "Blankenhorn and the Marriage Radicals".)

Apologies if I missed it, but I can’t find any acknowledgment from Blankenhorn of the marriage radicals’ deep unease with gay marriage, an unease that is present in the writings of even those marriage radicals who favor gay marriage. This is a significant and strange omission, one that henceforth opponents of gay marriage must know will not go unchallenged.

Blankenhorn may now say that the authors I have cited and the concerns they have expressed are a minority on the left. I don't know what the basis is for that claim, so I don't know how to assess it. But frankly, it is hard to credit such an observation when his book demonstrates no familiarity with these quite common anti-SSM concerns among marriage radicals.

And why do we care what marriage radicals think anyway? Though prolific in academic journals, they’re a small group and are not very influential in public policy. They won’t be able to control how heterosexuals or homosexuals think of their marriages or how they practice them. Gay marriage will have its effects, whatever they hope for.

Blankenhorn defends his reliance on their writings in his book this way (p. 128):

I believe that my nightmare can even be expressed as a sociological principle: People who professionally dislike marriage almost always favor gay marriage. Here is the corollary: Ideas that have long been used to attack marriage are now commonly used to support same-sex-marriage. (emphasis original)

We could have a lot of fun with “sociological principles” like that. How about this:

People who professionally dislike feminism almost always oppose gay marriage. Here is the corollary: Ideas that have long been used to attack feminism are now commonly used to oppose same-sex marriage.

Or this:

People who professionally dislike homosexuality almost always oppose gay marriage. Here is the corollary: Ideas that have long been used to attack homosexuality are now commonly used to oppose same-sex marriage.

(4) Blankenhorn challenges my claim that conservative supporters of SSM generally believe the following:

(1) marriage is not an outdated institution, (2) divorce should be made harder to get, (3) adultery should be discouraged and perhaps penalized in some fashion, (4) it is better for children to be born within marriage than without, (5) it is better for a committed couple to get married than to stay unmarried, (6) it is better for children to be raised by two parents rather than one

He thinks such people don’t really exist and asks me to name a prominent one. OK, here goes.

As I thought was clear in my post, I believe these six things (though I may not count as a “prominent” SSM supporter). Though I’d prefer to let him speak for himself, I know that Jon Rauch unequivocally supports 1, 4, 5, and 6. On 2, he certainly supports the goal of reducing the divorce rate, but isn’t sure how to do it. On 3, he supports discouraging adultery socially (“stigmatizing it,” as Blankenhorn aptly puts it), but doesn’t want the law to penalize it. And while Andrew Sullivan can certainly speak for himself, I also know that he supports all six, though he also doesn’t want the government investigating or penalizing people for adultery. (Like Rauch and Sullivan, I don't support criminalizing adultery but am open to proposals for attaching some form of civil disadvantage to it. I suggested as much reviewing William Eskridge's book Gaylaw six years ago.) I'd bet David Brooks, a conservative supporter of SSM, agrees with all or most of these ideas in some form — but I frankly haven't asked him. I’m certain there are others in this pro-SSM traditionalist camp. Maybe conservative pro-SSM writers and bloggers will challenge Blankenhorn's suspicion that they're a fiction.

Where have we said all these things? I don’t know that each of us has written about each of them in precisely these terms or in the somewhat different terms Blankenhorn insists we should have. But these views are at the very least implicit in the conservative case, and in some cases they've been made explicit. The conservative case for SSM is now almost 20 years old, going back to Sullivan’s pathbreaking New Republic article, and continuing through his book Virtually Normal, Rauch’s voluminous writings and book arguing that marriage should be the gold standard for commitment and raising children, and my own work.

I don’t have time to chase down sources and quotes for Blankenhorn, but for my own work he could start with the Traditionalist Case for Gay Marriage or look at some of the many columns I’ve written on the subject. If he really cares what I think, he can look forward to a law review article I'll be writing soon on traditionalism and gay marriage. I don’t know how one could come away from all this with the impression that I think marriage is outdated, that high divorce rates are good (I’ve criticized them in numerous debates on the subject with St. Thomas Professor Teresa Collett, BYU Professor Lynn Wardle, etc), that children’s well-being is unrelated to marriage, etc.

As Blankenhorn correctly puts it, we really do “operate[] from a very important shared intellectual and moral framework,” which is what makes the SSM debate among conservatives so much more interesting than the tired debates between the pro-SSM marriage radicals and anti-SSM marriage traditionalists. They really have nothing useful to say to each other. By contrast, I've suggested ten principles upon which conservatives, both pro- and anti-SSM, can agree. They give us a lot of common ground.

In conclusion (!), I wouldn’t usually use this many electrons responding to a single article or book. But Blankenhorn’s book is unusually well-written. And intellectual guilt-by-association has an easy appeal that may make his argument that these bad things all "go together" an anti-gay marriage mantra in the future. Like Kurtz’s superficially frightening correlations, now largely ignored on both sides of the debate, Blankenhorn's argument has to be carefully unpacked to show how unsatisfying it is.

P.S.: If you haven't had enough, see some further thoughtful comments about Blankenhorn's argument by St. Thomas Law School's Robert Vischer.

P.P.S.: Rauch has now finished reading Blankenhorn's book and calls it "the best piece of work that the anti-gay-marriage side has yet produced, containing much to admire despite its flaws."

P.P.P.S.: Maggie Gallagher weighs in: "The question is: what is the main idea SSM advocates are asking us to embrace and what implications over the long term will accepting this core idea about gay marriage have for our ideas about marriage in general?"

Dice-K's Debut:

In their ongoing struggle against the Empire, the Rebels have called on a new hope from far, far away. Today, he made an impressive debut. True, it was only one game, and against the weak Kansas City Royals. However, let us not forget that Luke Skywalker had to vanquish the incompetent Jabba the Hutt in order to prepare for his confrontation with the more formidable Emperor Palpatine. In time, "Dice-K" Matsuzaka may do the same with the Emperor Steinbrenner.

DOJ Computer Crime Manual:

The Justice Department's Computer Crime and Intellectual Property Section recently published a new manual, " Prosecuting Computer Crimes," that explains most of the federal computer crime statutes and analyzes sentencing and jurisdictional issues as well. I disagree with some of the positions adopted in the manual, but it's a very useful resource for those wanting to get started in the field. It's also essential reading if you're a defense attorney in a federal computer crime case and you want to know what positions the government is likely to adopt.

Gonzales Prepping for Senate Testimony:

From the front page of the Washington Post: Attorney General Alberto R. Gonzales has retreated from public view this week in an intensive effort to save his job, spending hours practicing testimony and phoning lawmakers for support in preparation for pivotal appearances in the Senate this month, according to administration officials.

After struggling for weeks to explain the extent of his involvement in the firings of eight U.S. attorneys, Gonzales and his aides are viewing the Senate testimony on April 12 and April 17 as seriously as if it were a confirmation proceeding for a Supreme Court or a Cabinet appointment, officials said.

Ed Gillespie, a former Republican National Committee chairman, and Timothy E. Flanigan, who worked for Gonzales at the White House, have met with the attorney general to plot strategy. The department has scheduled three days of rigorous mock testimony sessions next week and Gonzales has placed phone calls to more than a dozen GOP lawmakers seeking support, officials said.

. . .

"In a sense, this is even more difficult than a confirmation hearing, because you are defending a record that has been assailed publicly and it involves other members of Justice who are also going to be called," said former senator Daniel R. Coats (R-Ind.), who led confirmation preparations for Supreme Court Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr. and former White House counsel Harriet E. Miers.

"It just compounds the difficulty facing any witness in this situation," Coats said. "You don't have the ability to coordinate with other organizations or individuals that are going to be testifying, and there will be a lot of people looking for inconsistencies. It is no small challenge for the attorney general." When it's such a major challenge for an Attorney General to testify truthfully about what he himself did, it's probably time to get a new Attorney General.

Needless Abstractions:

While I'm on the topic of writing, I thought I'd bring up one of the most serious problems I find in legal writing (though I suspect it's common in other fields, too): Needless abstractions.

Generally speaking, arguments are most effective when they are made using words that clearly describe the real problems that people face, rather than using abstractions (even if the abstract terms aren't especially legalese). Consider the following phrases, from student papers I got in my firearms regulation seminar:

... when law enforcement is unavailable.

Considering the amount of violence that is connected with guns ...

... will have a positive effect.

They are written in fairly plain English, and aren't hard to understand -- but they make their points through abstract terms such as "unavailable," "violence," and "positive effect," and the circumlocution "law enforcement."

When you want someone to protect you, whom do you want? Your visceral, real-life answer will be "the police," not "law enforcement." What do you want them to do? Your normal answer will be "come in time," not "be available." "When the police can't come in time" quickly engages the reader's practical concerns; "when law enforcement is unavailable" doesn't. (I assume that the "[come in time] to prevent a killing, rape, or robbery" is implicit from context; if it isn't, then some such phrase should be included.)

"Considering the amount of violence that is connected with guns" is likewise not nearly as effective as "Considering how many people are killed, injured, or threatened with guns." Killings, injuries, and threats are what people really worry about; "violence" is just the abstract term for that. Readers will intellectually understand what "violence" means, but they won't be as engaged by it as they would be by "killed, injured, or threatened."

Similarly, instead of "will have a positive effect," it's much better to describe the actual effect, for instance "will prevent many murders and suicides." No one wants "positive effects" in the abstract; they want specific, concrete benefits, and if you explain the benefits, people will be more persuaded.

One more example:

The waiting period provides a vital time frame, which allows an individual the time to reconsider their actions and consequently, lives will be saved.

This sentence contains several writing glitches; "individual" is legalese for "person," "a vital time frame" is vague, and "their" is plural while "individual" is singular. But the deeper problem is that the sentence is written using unnecessary abstractions. A better formulation would be:

The waiting period can prevent impulsive murders and suicides, by giving people time to calm down [optional: and reconsider their plans].

Instead of the general "time to reconsider their actions" and "lives will be saved," this explains concretely which actions (impulsive murders and suicides) will be reconsidered and which lives will be saved. It provides more substantive details, describes a concrete scenario for the reader (an impulsive person needs to calm down, or else he'll commit murder or suicide), and thus makes the argument more persuasive.

There are two situations in which the concrete is not as good as the abstract. First, sometimes one needs to use a term that's more abstract but more precise. For instance, "murder" is usually a better, more concrete term than "homicide," but if one is talking about a study that measures all homicides (including manslaughter, justifiable homicide, and excusable homicide), one must use the more accurate term.

Second, sometimes one intentionally wants to soften the emotional force of a claim, either because the issue may be too viscerally engaging (part of the reason that some articles use "sexual assault" instead of "rape"), or because one is describing the other side's argument. This second reason is not entirely praiseworthy, but it may be tolerable; persuasive writers have an obligation to describe the counterarguments honestly, thoroughly, and clearly, but they need not frame them in the most emotionally forceful way possible.

But these are exceptions. The rule should be to talk about what actually matters to the reader (the police not coming in time) and not about abstractions (law enforcement being unavailable).

Passive Voice:

A recent usage thread turned to the old question of the passive voice. Many people recommend that you turn the passive voice -- "The action was done by this person" (the object was verbed by the subject) or just "The action was done" -- into the active voice, "This person did this action" (the subject verbed the object).

This is generally good advice. Passive voice often makes writing less direct and thus less forceful: "Passive voice should be avoided by you" is worse than "Avoid the passive voice." It also sometimes conceals responsibility, as in the famous "Mistakes were made" used as a substitute for "We made mistakes."

But when it comes to writing, unwise editors often turn good general advice into a bad categorical rule. So it is here: "Generally avoid the passive voice" is good, "never use the passive voice" is bad.

In particular, if your discussion focuses more on the object than on the subject (the actor), it's often better to use the passive voice, which has a similar focus. If you’re writing about the substance of the USA Patriot Act, for instance, the passive sentence "The Act was adopted shortly after the September 11 attacks" may be better than the active "Congress adopted the Act shortly after the September 11 attacks." The passive voice properly focuses the discussion on the Act, where you want it to be, rather than on Congress, which is not terribly relevant to your thesis. (Of course, if you were writing about Congressional decisionmaking related to the Act, "Congress adopted ..." may be exactly right -- but again the point is to choose the voice that fits what you want to emphasize, not to mechanically make everything active.)

Virtual Property:

There's a fascinating post over at Terranova -- a terrific blog on the legal, economic, and social environments in virtual worlds -- on Elizabeth Townsend Gard's experiment with her first year Property students, in which students make "expeditions" into Second Life to explore what the common law property concepts they're learning about in class (the law of finders, adverse possession, landlord-tenant law, etc.) look like in virtual space, and then they report back on what they've learned. The student projects are quite interesting, and the whole project is worth a good look, at least if you're interested in what "property law" might look like in 50 years or so . . .

[Thanks to Greg Lastowka for the pointer]

Privatization and the Law and Economics of Political Advocacy, Part 3 -- The Model:

This post continues my series on my upcoming Stanford Law Review paper on Privatization and the Law and Economics of Political Advocacy (see here for the technical paper). This installment is not connected to privatization specifically at all, much less prisons, but gives (in plain English) the basic economic theory behind public goods and free riding.

* * *

I now present the main model I use to predict how industry actors will react to privatization. The central feature of the model is that industry-increasing advocacy is a public good. Privatizing part of the industry therefore introduces a collective action problem: Unless everyone in the industry cooperates with each other, they will together spend less on industry-increasing advocacy than a single firm would if it covered the whole industry, because a portion of their expenditures will benefit their competitors.

This intuition should not be surprising, as it is standard in the literature on public goods. When a good is private, everyone pays for, and enjoys, only his own consumption. By contrast, when a good is public, in the classic model, everyone benefits from the total amount, and this amount is determined by the total amount of contribution.

If we benefit from our national defense, we benefit from the full amount, not from the chunk we paid for; we cannot be excluded from the full benefit, no matter how little we paid; and the total amount of national defense is just determined by how much money Congress allocated to national defense from the Treasury. A tax-funded program that improves air quality benefits everyone who breathes the relevant air, whether or not they contributed to the program; and the total improvement is just determined by the amount of resources directed toward that goal.

Similarly, contributing to a candidate’s campaign benefits all of his supporters; and it is not too implausible to say, as an approximation, that to the extent the money he raises and spends affects his probability of winning, it is only the total amount of money that matters.

In all these cases, the temptation to free ride off one’s fellows’ contributions is strong—so strong that the category of “public goods” is standard among economists as a case of “market failure.”

To explore the basic model, consider a monopolist, who's willing to invest some amount of money in lobbying to increase the size of his industry. To determine that amount, he weighs the benefit that his money can buy—the expansion of the industry is worth something to him, and money can help his policy pass—against the cost of the lobbying.

If that firm is broken up into two smaller firms—say a 90% incumbent firm and a 10% splinter firm—the larger incumbent isn’t willing to spend as much as it used to be, because the costs of lobbying are the same while the benefits are 10% less than they used to be. And the smaller splinter firm won’t be willing to spend anything, because it will be satisfied free-riding off the larger incumbent’s lobbying. Thus, splitting up an industry tends to decrease industry-expanding lobbying.

The rest of this post will illustrate this intuition graphically.

Suppose you are, as economists say, a rational, risk-neutral expected utility maximizer. One may dispute how much of life this assumption can explain, but on balance it seems to be at least a good starting point for predicting the behavior of business organizations. You are faced with the choice of whether or not to spend a dollar on political advocacy—donating to the campaign of a politician or voter initiative, contributing to your trade association’s lobbying expenses, or running an ad—in favor of some reform that could increase the size of your market. We may assume that this dollar has some influence in the world, whether appropriate or inappropriate—it could corrupt a legislator, raise the chance of his election, contribute to the passage of the initiative, or change popular opinion.

The benefit of this dollar is the value of the increased probability of getting your desired policy change. It is reasonable to think that spending money on advocacy is subject to decreasing marginal returns, so each additional dollar gets you less and less benefit. The cost of a dollar, on the other hand, is and remains $1, no matter how many of them you spend. As long as the benefit of an advocacy dollar is greater than $1, you continue spending; and you stop as soon as that benefit reaches $1. Finally, you settle on the optimal total amount of advocacy spending—say $1 million.

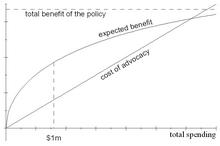

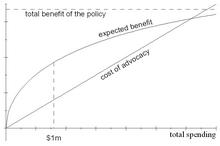

The picture below illustrates the situation. The expected benefit—that is, the probability of success times the benefit—is represented by the curved line below: The more you spend, the greater the probability of success, but the less you get for each extra dollar; and because a probability can’t get any higher than 1, the curve is bounded above by the dashed line representing the total benefit of the policy. The cost of advocacy is represented by the straight line below: Each dollar of advocacy costs $1. Your problem is to maximize the vertical distance between the expected benefit curve and the cost line. In the figure, that maximum distance occurs at a spending level of $1 million.

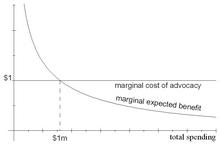

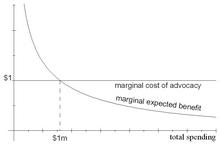

The next picture is an equivalent way of seeing the same problem. The curve below represents the marginal expected benefit—that is, the benefit of an extra dollar of spending, which is just equal to the total benefit times the extra probability that a dollar buys you. As noted above, the marginal benefit is decreasing. The straight line is the marginal cost of advocacy: An extra dollar of advocacy always costs $1. If the marginal expected benefit is above $1, you’re not spending enough; if it’s below $1, you should cut back. At a spending level of $1 million, an additional dollar of spending gives you exactly $1 of expected benefit.

Now suppose the Department of Justice’s Antitrust Division comes in and splits you up, so that you now have 90% of the market and are faced with a competitor with the other 10%. Your previous optimal amount, $1 million, is no longer optimal for you: The cost of that last dollar was $1, and while the benefit of the dollar is $1 for the whole industry, you, who now represent only 90% of the industry, only see 90¢ of that benefit. All your benefits are now lower by 10% because you have to share them with your competitor; for our purposes, the split-up thus has the same effect as a 10% tax on your benefit.

Because your spending on advocacy—an investment in the growth of your industry—is only 90% as productive, you do less of it. You start cutting back on your spending, because a dollar saved puts $1 back in your pocket and only reduces your benefits by 90¢. As you cut back more, the benefit of the last dollar rises; you stop cutting back as soon as the benefit of your last dollar to the industry reaches about $1.11 (which is a $1 benefit to you). Call the new amount $900,000.

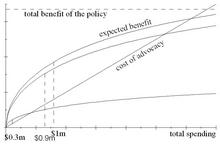

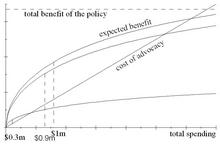

This new situation is illustrated in the next pictures. In the next one, the top curve is the expected benefit to the whole industry (as before), and the second curve is your expected benefit, newly reduced now that you only have 90% of the industry. The bottom curve is your 10% competitor’s expected benefit. The maximum vertical distance between your curve and the cost line now occurs at $900,000, and the maximum distance between your competitor’s curve and the cost line occurs at $300,000.

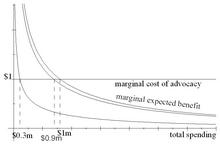

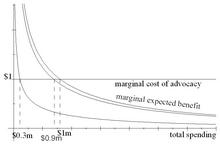

In the next picture, the equivalent graph that shows marginal quantities instead of total quantities, you want to find the point where the marginal expected benefit to the industry is $1.11. This is equivalent to finding the point where 90% of the marginal expected benefit (i.e., the benefit to you) is $1. That point is again $900,000. And your competitor wants to find the point where the marginal expected benefit to the industry is $10, which gives him $1; this is again $300,000.

This story is incomplete. You don’t want the amount spent to be exactly $900,000; obviously, you would be thrilled if other people happened to contribute more. It’s just that you’re not personally willing to put any dollar into the pot after the 900,000th. You want the total amount spent to be at least $900,000, and are willing to contribute money until that point is reached, but you stop being willing to personally contribute once you’re holding the 900,001st dollar.

This is because, in this model, the benefit of a dollar only depends on the total amount of money spent, and if the 900,000th dollar had a benefit to the industry worth $1.11 (and thus a benefit to you worth $1), then the 900,001st dollar has a benefit worth slightly less than $1.11.

Your new competitor, who represents the remaining 10% of the industry, and who is equally interested in this reform that will increase the size of the pie, wants the total amount spent to be at least $300,000, and won’t put a 300,001st dollar into the pot.

All this leads to two conclusions.

First, the total amount spent should not exceed $900,000. If it did, you would want to take some money out of the pot, since the dollars beyond the 900,000th are giving the industry a benefit below $1.11, and therefore giving you a benefit below $1.

Second, there’s no reason for your competitor to spend anything. He’s unwilling to spend any dollar beyond the 300,000th, since its marginal benefit to the industry is under $10, and so its marginal benefit to him is under $1. Thus, suppose you were going to spend $600,000 and he was going to spend $300,000. These actions would not be an equilibrium, since he would prefer to keep his $300,000. Why should he spend any extra dollar beyond the $600,000 you’re already spending, if the 300,001st dollar already isn’t worthwhile to him? The only equilibrium is where you give $900,000 and he gives $0. Because he’s the smaller actor, he totally freerides off you. The result is what Mancur Olson calls the “systematic tendency for ‘exploitation’ of the great by the small.”

Making the Daily Show:

Over at PrawfsBlawg, lawprof Jack Chin blogs about his experience being interviewed for a segment on the Daily Show. An excerpt: Probably their most effective technique was one that lawyers can't emulate: Editing together a question with an answer to an entirely different question. You see, they do the interview with a single camera; first, they ask all of the questions and tape the mark's answers, and then they tape the questions, sometimes doing multiple takes, so they have several versions from which to choose. So, a couple of questions went like this:

Question: Do you think it is important that everyone have the right to vote?

Answer: Very much so, yes sir.

Question: Does the Arizona Voter Rewards Initiative make you angry?

Answer: No, but I think it is a bad idea as a matter of policy.

On TV, it was like this:

Question: Does the Arizona Voter Rewards Initiative make you angry?

Answer: Very much so, yes sir.

The last thing the Daily Show team taught me was the value of an airtight release, which they made me sign at the beginning of the process. The document made clear that they were free to present me in a false light, so nothing they did was unexpected.

Wednesday, April 4, 2007

"Spousal unions" for same-sex couples pass New Hampshire House:

The vote was overwhelming and bipartisan, 243-129. The bill is limited to same-sex couples, who will have all the rights and restrictions of marriage. Attempts to include father-son and sister-aunt partnerships, etc., and opposite-sex couples, were defeated.

The bill moves to the state senate and then to the Democratic governor, who opposes gay marriage but hasn't spoken either way on civil or "spousal" unions.

New Hampshire would be the sixth state to grant full marital benefits to gay couples, and the third to do so purely legislatively, without an order from a court. All of the state-wide laws so far have been limited to same-sex couples (with an exception for elderly opposite-sex couples in California) and have applied the consanguinity and other eligibility restrictions of marriage.

UPDATE: A commenter makes an excellent catch. The actual legislation calls the new partnerships "spousal unions" — not "civil unions" — making it even harder to distinguish what the state is doing from marriage. I've adjusted the title and text of the post to reflect this. It's going to test some boundaries.

Some interesting questions to ask presidential candidates campaigning in New Hampshire and who've said they favor "civil unions," but not "marriage": Do you favor "spousal unions" for gay couples that give them all the rights and responsibilities of marriage but aren't called "marriages"?

And what if we take it the next step and called them "marital unions" but not "marriage"? This will test just what it is people think is at stake in the use of language to describe gay families.

Profile of Yale Law Dean Harold Koh:

The Yale Daily News has what strikes me as a balanced profile of Koh [the first of a two-parter], who is by all accounts a nice guy, a good fundraiser, and beloved by his students, but is also a highly partisan liberal Democrat under whose tenure as dean conservative and libertarian students have felt increasingly uncomfortable, and conservative and libertarian alumni have, at least in some cases (as noted in the Daily News piece) grown increasingly alienated.

The article paraphrases a post I wrote for the VC mentioning that, by contrast to when I was a student, Harvard Law School under Dean Kagan now has a reputation as a far friendlier place than Yale for Federalist Society types, and that Harvard is now much more open-minded than Yale about hiring non-liberals. While I don't object to the paraphrase, it would have been better form if the Daily News writer had made it clear that he never actually spoke to me, but just cribbed some comments from the VC.

Meanwhile, Professor Bainbridge piles on. Noting that Koh is on everyone's short list for the Supreme Court in a Democratic administration, Bainbridges predicts that "Koh's appointment to the SCOTUS would be an unmitigated disaster."

Columbia University Continues to Threaten to Use Eminent Domain to Expand into a Nearby Harlem Neighborhood:

Last year, I blogged about Columbia University's threats to use eminent domain to take over some land it covets in a the nearby Manhattanville neighborhood of Harlem. According to this New York Post article by urban development specialist Julia Vitullo-Martin (hat tip Candace de Russy), the University is continuing its threats:

The expansion of Columbia, already the city's seventh largest private employer, would add another 6,900 premium jobs - high pay, with generous benefits and pensions - to the local economy.

And the 17 acres on which the school hopes to build (bordered by 125th and 133rd streets, and by Broadway and Riverside Drive) are largely underused relative to the rest of Manhattan.

The sticking point is plainly Columbia's demand to get it all. Luisa Henriquez, who lives in a city-owned building on 132nd Street, puts it this way: "Columbia moving in is a bad thing because Columbia isn't willing to share."

"We're not going to take [eminent domain] off the table," says Columbia Executive Vice President Robert Kasdin. "We're going to preserve our right to argue to the state that it's in the public interest that they do it."

Yet even the strongest Harlem supporters of the Manhattanville plan, like realtor Willie Kathryn Suggs, balk. "I don't want them invoking eminent domain for private use. It's not right," says Suggs. "The neighborhood will get safer streets and better restaurants. I want that to happen. But under the rules. If they want more property they should buy it fairly, like anyone else."

And the opponents are ferocious. Manhattanville's largest private property owner, Nick Sprayregen, President of Tuck-It-Away Self-Storage, says that Columbia wants four of his five buildings . . . "My father built this business, which I intend to hand onto my children," he says. "We worked hard for the neighborhood, and intend to be part of its success.

"I won't move," Sprayregen insists. "But Columbia wants it all - 100 percent of everything. They have no desire for nuance, for compromise, for diversity."

The article notes that Columbia plans to argue that the area in question is "blighted." Under New York law eminent domain law, which is perhaps the most hostile to property rights of any in the country, almost any area can be declared blighted - and thereby subject to condemnation - no matter what its condition. As I noted in my original post, just a few years ago a New York appellate court held that Times Square was blighted, thereby permitting the condemnation of some property there for transfer to the New York Times for the purpose of building a new headquarters for the New York Times. Unfortunately, the use of blight standards broad enough to cover virtually any property is far from unique to New York, as I explained in more detail in this August 2006 Legal Times article. The retention of broadly defined blight statutes also undermines many of the reform laws enacted in the wake of Kelo v. City of New London (See my paper on post-Kelo reform, pp. 15-21).

Three other aspects of the Columbia/Harlem situation are symptomatic of broader flaws in eminent domain policy. First, this is just one of many cases where the power of eminent domain is used by wealthy and politically influential interests (in this case Columbia), at the expense of the poor and politically weak (here, the mostly poor and minority residents of Manhattanville). Second, as Columbia's lawyers surely know, even the mere threat of eminent domain often enables powerful interest groups to acquire land at a lower price than the owner would be willing to accept on the open market. For this reason, the misuse of eminent domain for the benefit of powerful interest groups is far more common than we might think if we focus only on takings that are actually carried out. Finally, like many would-be beneficiaries of eminent domain, Columbia claims that it needs to acquire 100% of the area in question and that eminent domain may be the only way to do so. Both claims are dubious, especially the latter. As I explain in some detail in this forthcoming article (pp. 21-29), there are numerous private sector alternatives to condemnation in cases where a developer seeks to acquire land for uses that really are more valuable than those of the present owners.

Perhaps Columbia's planned expansion really would benefit the local economy more than the present uses of the land in question. If so, it is highly likely that those benefits could be achieved without resorting to condemnation or using the threat of eminent domain to intimidate property owners into selling at a low price. And we should also keep in mind the fact that many "blight" and economic development condemnations actually damage local economies far more than they benefit them, as happened in the notorious 1981 Poletown condemnations, and also in Kelo v. City of New London (where some $80 million in public funds has been spent on a development project for little or no return). Once Columbia takes over the condemned land, it will not be under any legal obligation to actually provide the 6900 new jobs and other economic benefits that it is currently touting. As in many previous such cases, the new owner of condemned land could decide that providing the benefits it promised is not in its interest.

Justice Stevens' Scientific Mistake:

As Roger Pielke Jr. points out at Prometheus, there is a scientific error in Justice Stevens' Massachusetts v. EPA opinion:

there is a science error in the majority opinion, though it seems clear that it would not change their judgment of injury. It states:

. . . global sea levels rose somewhere between 10 and 20 centimeters over the 20th century as a result of global warming.

According to the IPCC’s Third Assessment Report this value is more like 3 to 5.5 centimeters (from figure 11.10b here) with the rest of the 10 to 20 centimeters total due to natural causes. The Supreme Court has attributed all sea level rise to global warming which is incorrect.

As Pielke goes on to note, this error is not particularly material to the majority's conclusions — it would have found standing even had it relied upon the correct estimates for warming's contribution to sea-level rise — but it is worth noting nonetheless. Related Posts (on one page): - Justice Stevens' Scientific Mistake:

- More Mass v. EPA Commentary:

Steve Simpson Responds to Comments on IJ Campaign Finance Report:

Last week I noted the new report from the Institute for Justice on state campaign laws and their impact on grassroots political activity. The post spurred many interesting Comments. Steve Simpson of IJ has provided a response to some of the comments and questions presented there.

I reproduce his response here (it is extensive, so I have hidden some of the text):

Your readers have raised a number of interesting points and questions about IJ’s study on disclosure in the ballot issue context on which I’d like to comment.

First, its important to be clear about our position. We support a free market in information. Disclosure should be between groups that speak out about ballot issues and their contributors. If some groups think disclosure is important, they can disclose their contributors and perhaps even make it an issue in the campaign. If reporters or voters favor it, they can call on groups to disclose. But the government should not require disclosure simply because people want to exercise their First Amendment rights.

That does not mean that no one will know who is behind a ballot initiative. Placing an issue on the ballot is a fairly detailed process. Someone must actually draft the language of the initiative, gather the necessary signatures, and go through the process to place the issue on the ballot. That person or group will obviously have to be disclosed.

But disclosure laws apply to more than just the sponsors of a ballot initiative.

For example, Colorado requires any group of “two or more people” who spend as little as $200 to “support or oppose” a ballot issue to register as an “issue committee” and comply with disclosure laws. That includes pretty much any group that wants to communicate effectively to voters about a ballot initiative. In my NRO piece, I gave the example of a small group of neighbors outside of Parker, Colo. who opposed the annexation of their neighborhood into the town. They didn’t intend to become a “campaign committee;” they simply intended to speak out about a ballot issue.

A few of your readers pointed out that people often support a ballot issue because they directly benefit from it. True enough. And others support ballot issues for philosophical or ideological reasons. But these are the same reasons that people exercise their rights to free speech, association, and their right to vote. There’s nothing corrupt about that. We have secret ballots because a person’s vote is their business, not ours. Why should exercising one’s right to associate by contributing to a group that speaks out about ballot issues be any different? As one of your readers put it, “I might be curious about who will benefit, but my curiosity does not create a right for me to know the answer.”

It would be interesting to know many things about those who support ballot issues. Would it not be useful to know that a ballot initiative concerning a state’s response to terrorism was supported or opposed primarily by Muslims? We could say the same thing about the age, sex, race and ethnicity, financial status, and sexual orientation of those who support various ballot issues. Why not compel the disclosure of that information as well?

Finally, one of your readers pointed to Ilya Somin’s post about an eminent domain “reform” initiative launched by the California League of Cities. The CLC seems to be capitalizing on the reform effort by property rights advocates and trying to pass of its initiative as something similar when it is not. So doesn’t disclosing who is behind the effort provide useful information to voters?