The existing political science literature tends to emphasize the loss of seats in Congress in midterm elections, which it nicely documents. In a comment to appear soon in the Yale Law Journal (vol. 115, pp. 2611-2622), Steve Calabresi and I document the loss of state governorships in off-year and midterm elections. You can download a full copy from SSRN at the bottom of this linked page.

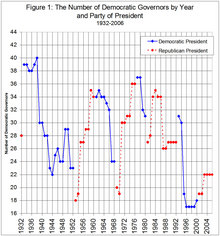

The backlash against the President's party in state races during a President's term is actually stronger overall than the coattail effect in the presidential election year. To be more specific, we find that four years after a party wins a presidential election, it holds on average three fewer statehouses than it had before it won the presidential election. Perversely, winning the presidency seems to lead very shortly to losing power in the states. Since 1932 there have been eight changes of party control of the White House (1933, 1953,1961, 1969, 1977, 1981, 1993, and 2001). In every instance but one, the party that seized the White House held more governorships in the year before it took office than in the subsequent year it lost the presidential election. The only exception is that in 1980, Republicans held four fewer governorships than they held in 1992, immediately before the Republicans were voted out of the White House. Similarly, of the eleven Presidents since 1933, every one except two, Kennedy and Reagan, left office with fewer governorships than his party had before he took office, and Kennedy served less than three years. Figure 1 shows this pattern.

Click to enlarge

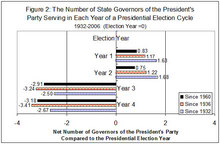

The four-year pattern of a federal election cycle is shown in Figure 2.

Click to enlarge

We attribute this effect to presidents being a lightning rod for everything that goes wrong, which tends to lead to lower presidential approval ratings:If one looks at the pattern since 1960, in his first year in office, a President's party controls only one more governorship than the party had in the election year. Once he is in office, there is a backlash against the sitting President's party. On average, since 1960, by the third and fourth years of a four-year presidential administration, the President has lost four seats from his first year, thus losing not only that one "coattail effect" seat, but three more governorships as well. One sees a similar, but slightly stronger, pattern since 1936. If one looks at just two-term administrations since the 1950s, by the seventh year of the administration, the party winning the White House has nearly eight (7.6) fewer governorships on average than it had before it won the White House.

Further, the lower voter turnouts for off-year and midterm elections tend to give those who are motivated to vote a bigger influence, and dissatisfaction with the president in office is a potential motivation.Most Presidents leave office less popular than when they entered, with Ronald Reagan and Bill Clinton being the only exceptions since at least Dwight Eisenhower. Even the exceptions (Reagan and Clinton) suffered major congressional losses in their first midterm elections, at times when their job approval ratings were down substantially. Thus, the response of voters is to blame the President for whatever goes wrong and, probably as a result, to punish that President's party in midterm and off-year elections.

Most states—-and all of the big ones—-have moved to electing their governors in off-year and midterm elections, in part to decrease the influence of the presidential election cycle on the state elections. Our data suggest that this effort to avoid presidential influence has been unsuccessful.

Theoretically, our backlash/lightning rod thesis is in some respects consistent and in some respects at odds with the prevailing political science theories of midterm elections: (1) referendum theory and (2) surge and decline/coattail theory.

As has been common with my other collaborations with Steve Calabresi, my contribution to the Yale comment has been predominately empirical (and to a lesser extent, theoretical).

The 2002 midterm election was unusual in Congress because the party not holding the White House, the Democrats, lost some ground, though they gained three governorships. The perhaps analogous 1962 election (which took place only a week or so after the Cuban missile crisis) was also relatively kind to the party in the White House, but the Democrats in power did very poorly in the next midterm election, 1966. Usually, in a two-term presidency, either the first or the second midterm election (1938, 1950, 1954, 1958, 1966, 1974, 1982, 1994) is very damaging to the president's party in either Congress or the states or both.

Before commenting below, please at least skim the paper itself (it is only 12 pages long):

Steven G. Calabresi and James Lindgren, The President: Lightning Rod or King?, 115 Yale Law Journal 2611, 2611-2622 (2006) (which may be downloaded at the bottom of this linked page at SSRN).